Friday, November 03, 2006

Free Agency Time...

Thanks to locking up younger players in multi-year contracts, the Phillies haven’t had a significant free agent defection in years. Thus far this season six Phillies have made the move to file for free agency. I’ll give a quick overview of how they did and what the Phillies ought to do.

David Dellucci – I am a big fan of David Dellucci. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter last season, Dellucci got to play regularly down the stretch once Bobby Abreu left for the Yankees and the Phillies decided they had little faith in Pat Burrell. Dellucci swings a good bat: he had a .530 slugging percentage with 13 home runs and 32 extra-base hits in just 301 plate appearances, and about a fifth of those were pinch-hitting situations, which are always difficult to do (coming into a game cold, the pressure to get a hit). Dellucci is also a good fielder and did a nice job replacing Burrell and Abreu. I'd love to see him back as a Phillie in 2007. If the Phillies can ship Burrell out this off-season, I'd love to see Dellucci slide into his spot as the Phillies everyday left fielder. He made just a little under a million bucks in 2006. I don't see why the team can't have him back for a little more than that.

Arthur Rhodes – Arthur Rhodes threw 45 & 2/3 innings for the Phillies in 2006 before being injured and vanishing for most of the season. Rhodes was expected to be the Phillies main set-up man for Tom Gordon, but things didn’t work out that way. When Arthur did pitch, he didn’t pitch well: allowing a 5.32 ERA with an 0-5 record. Rhodes is going to be 37 next season and I don’t see the utility in trying to re-sign him for 2007, especially at the salary he got last season: $4.8 mil. Let him walk.

Aaron Fultz – I like the job Aaron Fultz has done for the Phillies over the last two seasons: working as a set-up man, Fultz contributed 70+ solid innings of work the last two seasons. While Aaron’s ERA spiked from 2.24 to 4.54, his Fielding Independent Pitching ERA (FIP) remained constant at 3.64 to 3.68, very good numbers. Fultz made roughly $1.2 million last season, so I think it would be worth it for the team to try and bring him back.

Rick White – Rick White came over to the Phillies mid-season from the Cincinnati Reds and pitched decently well, only allowing three home runs in 37 & 1/3 innings of work. He’d be worth re-signing, given that his salary for 2006 was just $600,000 and he could probably be gotten for something similar.

Randy Wolf – Randy Wolf came back from Tommy John surgery and proceeded to go 4-0 with a 5.56 ERA in 2006. I’m really torn about trying to bring Wolf back, because oftentimes pitchers who undergo Tommy John surgery come back greatly improved in their second campaign after the surgery, but I worry that Randy isn’t worth the $6.6 million that the Phillies spent on him in 2006. To put it bluntly, his 4-0 record is a mirage. He didn’t pitch well at all: his FIP was 6.39. He gave up 13 home runs in 56 & 2/3 innings of work. He gave up five walks every nine innings he pitched. Based on those stats, bringing him back would be a mistake, but you have to factor in Wolf’s past: he’s been a solid pitcher for the Phillies. The team that signs him might get a great, All-Star caliber pitcher, but I don’t think the Phillies can take the chance, not with big new contracts being needed for Ryan Howard and Cole Hamels. Let Randy walk.

Mike Lieberthal – I really hate myself for what I am about to say, but the Phillies need to let Lieberthal walk. His 2006 price tag – $7.5 mil – is just way too high, and the Phillies have less pricey options waiting in the wings. Oft-injured in 2006, the Phillies played Sal Fasano before dealing him to the Yankees – who wanted him for some strange reason – and going with the platoon of rookies Chris Coste and Carlos Ruiz. Coste and Ruiz both played very good baseball and suggested that they could platoon and give the Phillies good production from the catchers slot.

Runs Created / 27 Outs:

Lieberthal: 5.0

Ruiz: 5.4

Coste: 7.3

Oh, and Ruiz and Coste together cost the Phillies $654,000 in 2006, far less than what they paid Mike Lieberthal, who turns 35 in January. I hate to say it, because Lieberthal had played so well and is such a competitor, but I think the Phillies need to let him walk.

The A.L. Gold Gloves were announced yesterday and, as usual, baseball decided to ignore fact and evidence and award the Gold Glove for short to Derek Jeter. What exactly is the criteria for a Gold Glove anyway? I ask because Jeter falls short on every demonstrable fact I know of. Sigh. Let's hope the N.L. gives Chase Utley his today

Anyway, enjoy the weekend. Monday check in for Part 1 of my Season in Review series. I’m talkin’ my favorite subject: Fielding. Tuesday I am taking a break from baseball to predict the election results, then Wednesday I am back to the Wiz Kids with Part XII, the climatic game between the Phillies and Dodgers on October 1, 1950, that saw the Phillies take the pennant in dramatic fashion. Thursday I’ll break down how the Phillies won the N.L. in 1950.

(2) comments

David Dellucci – I am a big fan of David Dellucci. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter last season, Dellucci got to play regularly down the stretch once Bobby Abreu left for the Yankees and the Phillies decided they had little faith in Pat Burrell. Dellucci swings a good bat: he had a .530 slugging percentage with 13 home runs and 32 extra-base hits in just 301 plate appearances, and about a fifth of those were pinch-hitting situations, which are always difficult to do (coming into a game cold, the pressure to get a hit). Dellucci is also a good fielder and did a nice job replacing Burrell and Abreu. I'd love to see him back as a Phillie in 2007. If the Phillies can ship Burrell out this off-season, I'd love to see Dellucci slide into his spot as the Phillies everyday left fielder. He made just a little under a million bucks in 2006. I don't see why the team can't have him back for a little more than that.

Arthur Rhodes – Arthur Rhodes threw 45 & 2/3 innings for the Phillies in 2006 before being injured and vanishing for most of the season. Rhodes was expected to be the Phillies main set-up man for Tom Gordon, but things didn’t work out that way. When Arthur did pitch, he didn’t pitch well: allowing a 5.32 ERA with an 0-5 record. Rhodes is going to be 37 next season and I don’t see the utility in trying to re-sign him for 2007, especially at the salary he got last season: $4.8 mil. Let him walk.

Aaron Fultz – I like the job Aaron Fultz has done for the Phillies over the last two seasons: working as a set-up man, Fultz contributed 70+ solid innings of work the last two seasons. While Aaron’s ERA spiked from 2.24 to 4.54, his Fielding Independent Pitching ERA (FIP) remained constant at 3.64 to 3.68, very good numbers. Fultz made roughly $1.2 million last season, so I think it would be worth it for the team to try and bring him back.

Rick White – Rick White came over to the Phillies mid-season from the Cincinnati Reds and pitched decently well, only allowing three home runs in 37 & 1/3 innings of work. He’d be worth re-signing, given that his salary for 2006 was just $600,000 and he could probably be gotten for something similar.

Randy Wolf – Randy Wolf came back from Tommy John surgery and proceeded to go 4-0 with a 5.56 ERA in 2006. I’m really torn about trying to bring Wolf back, because oftentimes pitchers who undergo Tommy John surgery come back greatly improved in their second campaign after the surgery, but I worry that Randy isn’t worth the $6.6 million that the Phillies spent on him in 2006. To put it bluntly, his 4-0 record is a mirage. He didn’t pitch well at all: his FIP was 6.39. He gave up 13 home runs in 56 & 2/3 innings of work. He gave up five walks every nine innings he pitched. Based on those stats, bringing him back would be a mistake, but you have to factor in Wolf’s past: he’s been a solid pitcher for the Phillies. The team that signs him might get a great, All-Star caliber pitcher, but I don’t think the Phillies can take the chance, not with big new contracts being needed for Ryan Howard and Cole Hamels. Let Randy walk.

Mike Lieberthal – I really hate myself for what I am about to say, but the Phillies need to let Lieberthal walk. His 2006 price tag – $7.5 mil – is just way too high, and the Phillies have less pricey options waiting in the wings. Oft-injured in 2006, the Phillies played Sal Fasano before dealing him to the Yankees – who wanted him for some strange reason – and going with the platoon of rookies Chris Coste and Carlos Ruiz. Coste and Ruiz both played very good baseball and suggested that they could platoon and give the Phillies good production from the catchers slot.

Runs Created / 27 Outs:

Lieberthal: 5.0

Ruiz: 5.4

Coste: 7.3

Oh, and Ruiz and Coste together cost the Phillies $654,000 in 2006, far less than what they paid Mike Lieberthal, who turns 35 in January. I hate to say it, because Lieberthal had played so well and is such a competitor, but I think the Phillies need to let him walk.

The A.L. Gold Gloves were announced yesterday and, as usual, baseball decided to ignore fact and evidence and award the Gold Glove for short to Derek Jeter. What exactly is the criteria for a Gold Glove anyway? I ask because Jeter falls short on every demonstrable fact I know of. Sigh. Let's hope the N.L. gives Chase Utley his today

Anyway, enjoy the weekend. Monday check in for Part 1 of my Season in Review series. I’m talkin’ my favorite subject: Fielding. Tuesday I am taking a break from baseball to predict the election results, then Wednesday I am back to the Wiz Kids with Part XII, the climatic game between the Phillies and Dodgers on October 1, 1950, that saw the Phillies take the pennant in dramatic fashion. Thursday I’ll break down how the Phillies won the N.L. in 1950.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

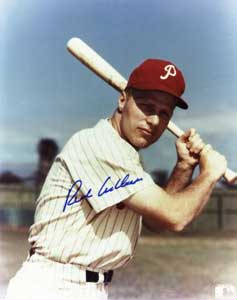

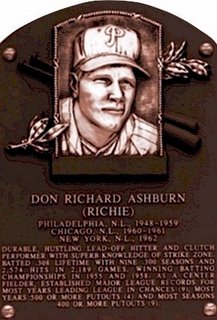

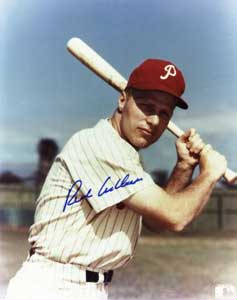

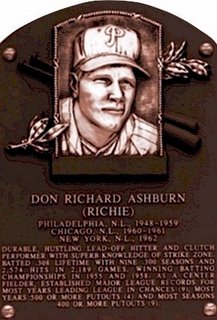

The Wiz Kids, Part XI: Richie Ashburn

It is a remarkable thing that Richie Ashburn wasn’t inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame u ntil 1995. It had been some thirty-three years after he stopped playing baseball before the Hall of Fame realized the tremendous mistake they had made and elected Ashburn to the Hall. Richie Ashburn is probably the most memorable player from the Wiz Kids, even more remembered than Robin Roberts.

ntil 1995. It had been some thirty-three years after he stopped playing baseball before the Hall of Fame realized the tremendous mistake they had made and elected Ashburn to the Hall. Richie Ashburn is probably the most memorable player from the Wiz Kids, even more remembered than Robin Roberts.

While not a slugger like fellow 1950s centerfielders Duke Snider or Willie Mays, Richie Ashburn had a remarkable career and deserves to be remembered as one of the all-time greats. Today Ashburn would probably be an eagerly sought player for his defensive skills and talent for getting on base. In the 1950s he largely played in the shadow of Mays and Snider, much flashier players who delivered what people wanted in the 1950s: home runs. Despite Ashburn’s remarkable play in the 1950s, he was an All-Star just five times in fifteen seasons. (interestingly, Ashburn was selected to the All-Star game in both his first season and in his last.)

All Richie Ashburn did for fifteen exceptional seasons was be the most consistent table-setter in baseball, as well as be one of the best defensive players in the game. Though he never finishing higher than seventh in the MVP voting (in 1951 and 1958), Ashburn led the N.L. in On-Base Percentage (OBP) four times: 1954, 1955, 1958 & 1960. Ashburn also led the N.L. in Batting Average twice: in 1955 and 1958. He finished in the top ten in runs scored seven times, the top ten in hits nine times, and finished in the top ten in times on base for eleven seasons. Richie Ashburn as a tough out, a tenacious defender and a true gentleman. According t o the Bill James Historical Abstract, “Richie Ashburn combined the Pete Rose virtues and the Pete Rose style of play with the virtues of dignity, intelligence and style.” (Historical Abstract, page 735.)

o the Bill James Historical Abstract, “Richie Ashburn combined the Pete Rose virtues and the Pete Rose style of play with the virtues of dignity, intelligence and style.” (Historical Abstract, page 735.)

Alright, I am going to stop and give you a quick primer on the stats I will be talking about in this article, lest you be baffled about what I am talking about and quit reading:

Gross Productive Average (GPA): (1.8 * .OBP + .SLG) / 4 = .GPA. Invented by The Hardball Times Aaron Gleeman, GPA measures a players production by weighing his ability to get on base and hit with power. This is my preferred all-around stat.

Isolated Power (ISO): .SLG - .BA = .ISO. Measures a player’s raw power by subtracting singles from their slugging percentage.

On-Base Percentage (OBP): How often a player gets on base. (H + BB + HBP) / (Plate Appearances)

Slugging Percentage (SLG): Total Bases / At-Bats = Slugging Percentage. Power at the plate.

Base Runs: A stat originally created by Dave Smyth to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. Here is the formula: A: H + BB + HBP – HR; B: (.8 * 1B) + (2.1 * 2B) + (3.4 * 3B) + (1.8 * HR) + (.1*(BB + HBP)); C: AB – H; D: HR; Then simply divide B into B + C, then multiply A to the result and add D.

Runs Created (RC): A stat created by Bill James to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. Runs Created was a stat James came up with in the 1970s that revolutionized our understanding of hitting stats. The formulas for each era are different because different stats were kept track of. Prior to 1950, for example, baseball didn’t keep track of caught stealing. Here is the formula for 1950, to give you an idea about what RC measures: [(H + BB + HBP - GIDP) times (Total Bases + .26 * (BB + HBP) + .52 * Sac Hits] divided by (AB + BB + HBP + SH).

Alright, back to the story.

Richie Ashburn was born in Tilden, Nebraska, in 1927. Eagerly sought after by baseball scouts, the St. Louis Cardinals and Chicago Cubs both attempted to sign Ashburn and failed due to his young age, which prohibited him from signing any contracts. The Cleveland Indians did sign Ashburn to a contract when he was sixteen, but the deal was voided by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis and Ashburn was declared a free agent. Later the Yankees and Phillies competed for his services and Ashburn elected to sign with the Phillies in 1945 for less money ($3,500) because he seemed more likely to get to play quicker. Ashburn went to the Phillies farm club in Utica under the watchful eye of Eddie Sawyer. Originally a catcher, Sawyer wisely moved Ashburn to centerfield. It was decided that the Phillies would promote Ashburn to the team for the 1948 campaign.

Richie’s problem was that the Phillies centerfielder was Harry “The Hat” Walker, the NL batting champion for 1947. The chances of Ashburn dethroning the thirty-year old Walker seemed remote, until Walker did Ashburn a favor by deciding to hold out for more money prio r to the 1948 season. When Walker did return to the team he was promptly injured due to his poor conditioning and soon found himself out of a job. Richie had seized the position of centerfielder and leadoff hitter and ran off with it. In his first season in the majors, Richie was a phenomenon:

r to the 1948 season. When Walker did return to the team he was promptly injured due to his poor conditioning and soon found himself out of a job. Richie had seized the position of centerfielder and leadoff hitter and ran off with it. In his first season in the majors, Richie was a phenomenon:

.333 BA / .410 OBP / .400 SLG

Richie’s GPA was a tremendous .285. He created 82 runs for the Phillies in 1950, or 7.04 per 27 outs. His batting average was second in the NL to Stan Musial and his OBP was third. He had a twenty-three game hitting streak at the start of the season, then a record for rookies, and he never looked back. Harry The Hat was history.

Ashburn’s secret at the plate was his amazing bat control. Ashburn struck out in just 5% of his At-Bats in 1948. Ashburn finished his career with a 2.09 BB to K ratio. He walked 1,198 times and struck out just 571 times. He would strikeout in just 7% of his career At-Bats. He had a great eye and put the ball into play with stunning frequency. Ashburn was also fast, an asset not often prized in 1950s baseball. Ashburn frequently bunted and beat out the throws to first for hits. He also led the NL in stolen bases with 32 in 1950. Ashburn said: “A good leadoff hitter is a pain in the ass to pitchers.” (The Quotable Baseball Fanatic at 44.) Richie was a tremendous pain in the ass of opposing pitchers. Despite being sidelined for the rest of the season in August with a broken finger, Ashburn was the Rookie of the Year in 1948.

Ashburn’s family came to live in Philadelphia with him and operated a boardinghouse where teammates like Curt Simmons and Robin Roberts stayed. Ashburn struggled in 1949, partly due to what he called “swelled head”. He came back in 1950 with a terrific season, hitting .372 OBP with 91 Runs Created (5.66 per 27 outs). He terrific catch and throw in the October 1, 1950, game against the Dodgers was the great, defining moment of Ashburn’s career. (See, Part XII.)

Unfortunately, Ashburn’s sole World Series appearance was a bust. He went three-for-seventeen against the Yankees without a walk (.176 OBP). Ashburn managed just a double and two singles. He had one of the Phillies three RBIs, a sacrifice fly in the fifth inning of game two, which tied the game at 1-1. (The Phillies would go on to lose 2-1 after DiMaggio hit a home run in the top of the tenth inning.)

The next year, 1951, Ashburn had his best season since ’48, finishing second in batting average at .344 and leading the league in hits with 221. He had 118 Runs Created (101 Base Runs) and 7.07 Runs Created per 27 outs. Richie had his best year in the MVP voting in 1951, finishing seventh. He followed the 1951 campaign with a sub-par year in 1952, hitting “just” .362 OBP. At the age of just 25, Richie Ashburn was the veteran of five major league seasons:

Richie Ashburn (1948 – 1952)

Runs Created / RC27

1948: 82 / 7.04

1949: 82 / 4.55

1950: 91 / 5.66

1951: 118 / 7.07

1952: 86 / 4.93

Base Runs / BsR27

1948: 76 / 6.48

1949: 76 / 4.22

1950: 87 / 5.37

1951: 101 / 6.09

1952: 77 / 4.41

GPA:

1948: .285

1949: .242

1950: .268

1951: .283

1952: .252

From 1953 to 1958 Richie Ashburn had his most productive seasons with the Phillies. He led the NL in batting average in 1953 and 1958. He also led the NL in OBP in 1954, 1955 and 1958. Richie led the NL in walks in 1954, 1957 and 1958. Whitey was an absurdly consistent player, hitting well over the team average for On-Base-Percentage every year during this time. Each season Richie’s OBP was sixty to one hundred points over the team average. He was a machine, getting on base and playing great defense (more on that later).

Richie Ashburn (1953 – 1958)

Runs Created / RC27

1954: 113 / 7.47

1955: 120 / 8.79

1956: 105 / 6.32

1957: 99 / 5.77

1958: 135 / 8.47

Base Runs / BsR27

1954: 103 / 6.80

1955: 113 / 8.29

1956: 93 / 5.58

1957: 93 / 5.38

1958: 123 / 7.71

GPA:

1954: .292

1955: .314

1956: .269

1957: .267

1958: .308

Despite being more of a table-setter on the Phillies offense, instead of an RBI slugger like Del Ennis, Whitey was a vital part of the Phillies offense. Without him getting on base for Ennis and Granny Hammer, the Phillies would have had a punchless offense during those Wiz Kids days. To give you an idea about how vital Ashburn’s skills at getting on base were to the Wiz Kids, look at what percentage of the Phillies total Runs Created Ashburn accounted for:

1954: 16%

1955: 17%

1956: 16%

1957: 16%

1958: 18%

These are tremendous numbers when you consider that Ashburn almost never hit home runs. This was purely a product of his exceptional ability to get on base, steal bases and leg out doubles and triples.

Statistically, Ashburn’s best season was 1958. Here is a brief snapshot of that season:

Batting Average: .350 (First in N.L.)

On-Base Percentage: .440 (First in N.L.)

Slugging Percentage: .441

ISO: .091

GPA: .308

Hits: 215 (First in N.L.)

Doubles: 24

Triples: 13 (First in N.L.)

Stolen Bases: 30 (Second in N.L.)

Walks: 97 (First in N.L.)

BB/K ratio: 2.02

Total Bases: 271 (Eighth in N.L.)

In addition to making the All-Star team that season, Ashburn had his best season since 1951 in the MVP voting, once more finishing seventh. The pity was that while he was performing so well the Phillies floundered, doing no better than fourth and winning just .457 of their games during this period (398-472). Each season the Phillies never factored in the pennant race, finishing eighteen to twenty-three games out of first, which was usually occupied by the Brooklyn Dodgers. In 1958, Ashburn’s finest season, statistically, the Phils went 69-85 (.448) and finished dead-last, twenty-three games out of first place. It was the first time that the Phillies had finished in the cellar since 1947.

Richie Ashburn had a terrible campaign in 1959. His batting average crashed eighty-four points from .350 to .266. His OBP declined eighty points. His slugging percentage went down one hundred and thirty four points as well. After stealing thirty bases in forty-two attempts in 1958, Richie stole just nine in twenty tries in ’59. After hitting thirteen triples in 1958, he hit just two in 1959. Ashburn played like half the player he was. After having 135 Runs Created in 1958, Ashburn produced just 70 in 1959. He was about half as productive for the Phillies:

RC/27:

1958: 8.47

1959: 4.26

He went from being 18% of the Phillies Runs Created to 12%. The Phillies once more finished twenty-three games out of it. With Ennis gone, and Hammer, Jones, Simmons and Roberts all in decline, the Phillies were intent on cleaning house. The decision to deal Richie Ashburn was an easy one for the team, positive that his best days were long behind him.

Naturally, the Phillies were wrong. Dealt to the Cubs in January of 1960, Ashburn had a terrific season in 1960, drawing 116 walks and upping his OBP to .415 at the age of thirty-three. He regained some of the speed he lost, successfully stealing sixteen bases in twenty attempts. However, the years had taken a little wear and tear: Ashburn appeared in just ninety-nine of the Cubs 154 games. The next season he played in just forty-nine for the Cubs and out the door again.

Richie found his way to the New York Mets, the infamous 1962 expansion team that set the bar for futility with a 40-120 record. The ’62 Mets were a remarkable team, sporting two 20+ game losers (Roger Craig at 10-24, and Al Jackson at 8-20), and a lovable collection of talent-less misfits and over-the-hill veterans. Richie Ashburn was supposed to have been one of those over-the-hill vets, but he turned out to be a real gamer in 1962. At the age of thirty-five, in his fifteenth major league season, Richie Ashburn turned in a sterling performance and was selected to the 1962 NL All-Star team. Whitey’s .424 OBP was the fourth-best of his career and almost thirty points better than his career average. He also posted a career high in home runs with seven and successfully stole twelve bases in nineteen attempts. His walk-to-strikeout ratio was better than two-to-one (81 to 39). He was still a major threat. You have to shutter to think of what the Mets record would have been without Richie Ashburn.

Next I am going to direct my attention to a particular facet of Ashburn’s game: fielding. People who read this blog know that I am fascinated by fielding and consider this to be my little niche in the Phillies blogging community. Nobody talks about D like me, in part because it is such a little understood aspect of the game. My favorite quote on the subject comes, not surprisingly, from Bill James, who wrote: “Hitting is solid, pitching is liquid and defense is gaseous … damned hard to capture, formless and hard to see.”

It is hard to clearly assess Richie Ashburn’s total contribution to the Phillies defense, but it is clear to me that he was one of the best there was and his contributions are undervalued by the baseball community. Wrote Bill James: “Ashburn was regarded while active as a fine defensive center fielder, but hardly as a sensation – certainly Willie Mays was thought to be better. Ashburn’s defensive statistics, then, are the subject of unending argument among people … whom are convinced that Ashburn really was that good but the contemporary observers just overlooked him because he didn’t play in New York …” (Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame at 327.) I certainly would fall into that category. One of the things that I feel is that the Wiz Kids never got their proper historical due because they weren’t the Dodgers or the Giants (i.e., they didn’t play in one of the five boroughs of New York), and I particularly feel that Richie Ashburn’s remarkable defensive achievements are badly, badly undervalued. For the only time in my life, I would agree with George Will, who devoted two pages (276 & 277) of his 1990 book Men At Work to complain about the Hall of Fame’s decision to exclude Richie. Wrote Will: “Why is a double denied on defense so much less admirable than a double delivered on offense? … [Ashburn and the Pirates great Bill Mazeroski] may not rank with Dreyfus on the list of history’s great victims, but the undervaluing of defense does say much about the standard measures of baseball excellence. And it says much about the misunderstanding of how games are won.”

Ashburn led the N.L. in putouts every season between 1949 and 1958 but one season (1955, when he played 140 games instead of 154). Richie led the N.L. in putouts by an outfielder nine times, a record he shares with the Pirates Max Carey, who led the N.L. in 1912-1913, 1916-1918 and 1921-1924. He led the N.L. in assists three times and led the N.L. in double plays three times. In his Historical Baseball Abstract Bill James notes that Ashburn’s Fielding Percentage is better than contemporaries like Wille Mays and Mickey Mantle. James, in particular, was impressed that Ashburn made five of the top nine all-time putouts in a season, despite playing just 154 games a year. (Page 326.) However James wonders if this is partly due to the fact that Robin Roberts and the Phillies pitchers were flyball pitchers, but even so it is impressive. The National League record for putouts in a season is 547, set by the St. Louis Cardinals Taylor Douthit in 1928. Richie’s career best is 538 in 1951, just nine fewer. If Richie had played in the American League he’d be the all-time league-leader: the A.L. record is 512, set by the White Sox Chet Lemon in 1977. More specifically, Richie would occupy the #1 & #2 slots: in addition to his 538 putouts in 1951, he also notched 514 in 1949. All during these years the Phillies were one of the best defensive teams in the National League. In 1950 they were the second-best in the N.L. in terms of Defense Efficiency Ratio (DER), which measures the percentage of plays where fielders turn balls put into play into outs. Richie was the major reason why they were so good for so long. Little surprise then that the season after Richie left to join the Cubs the Phillies fell to dead-last in DER. I think Ashburn’s effect on the Phillies is best summed up by temmate Robin Roberts: “I was fortunate as a pitcher. I had terrific defensive players behind me … the best of all was Richie [Ashburn]. I can’t tell you how many games I won with his glove and speed.” (Legends of the Phillies, page 16.)

Here are Richie’s putouts and assists season-by-season:

Put-Outs / Assists

1948: 344 / 14

1949: 514 / 13

1950: 405 / 8

1951: 538 / 15

1952: 428 / 23

1953: 496 / 18

1954: 483 / 12

1955: 387 / 10

1956: 503 / 11

1957: 502 / 18

1958: 495 / 8

1959: 359 / 4

1960: 317 / 11

1961: 131 / 4

1962: 187 / 9

Career: 6,084 / 174

According to James, after his injured his arm in 1951 Ashburn’s throws were slower and less powerful. However, Ashburn “compensated with quickness and positioning, and led the league in baserunner kills in 1952, 1953 and 1957.” (The Bill James Historical Abstract at 734.) I think that fact is a powerful argument for Ashburn’s greatness as well: he was quick and fast and very, very smart.

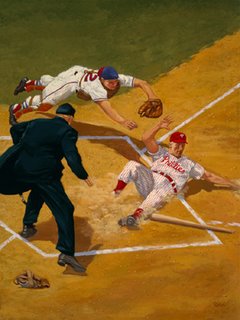

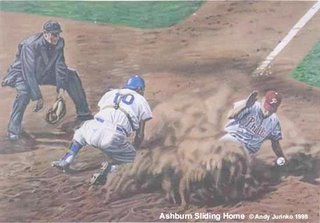

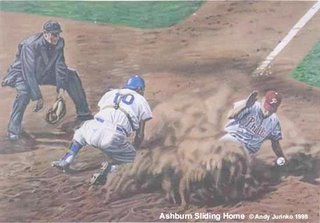

The single play that Richie Ashburn is most known for, of course, is his throw in the bottom on the ninth of the final game of the 1950 season against the Dodgers. I’ll discuss it a little more in Part XII, but the basic facts were that the Dodgers and Phillies were tied at 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth inning. If the Dodgers won, they’d force a playoff series with the ragged Phillies, who entered the game with a five game losing streak. With runners on first and second and no outs, Duke Snider got a hit right up the middle of the field. The Dodgers waved home Cal Abrams, who was rounding third from second base, while Richie Ashburn, who was playing shallow, moved in, scooped up the ball and hurled it to home, where catcher Stan Lopata tagged Abrams out by fifteen feet. Instead of winning the game 2-1 and forcing the playoff series, the Dodgers ended up failing to score a run and losing the game on Dick Sisler’s three-run home run in the top of the tenth inning. Ashburn’s quick reflexes and quick throw saved the Phillies the pennant.

It was such a tremendous play, such a tremendous moment, that Bill James felt it would have been one of the great moments in baseball history, had it not been for the fact that the very next season Bobby Thomson hit the climatic home run against the Dodgers to cap the ’51 playoffs, this game and Ashburn’s throw might be immortalized as one of the great moments in the history of the game. Certainly, had Thomson not obliterated the memory of the '50 pennant race, it would have sped Ashburn’s ascent to the Hall of Fame. And how appropriate that Ashburn’s greatest play was a defensive one?

For my post on Robin Roberts I gave an overview of his career via win shares by season. I’ll do the same for Richie:

Win Shares:

1948: 21

1949: 19

1950: 23

1951: 28

1952: 21

1953: 26

1954: 26

1955: 29

1956: 28

1957: 26

1958: 28

1959: 14

1960: 22

1961: 6

1962: 11

Career Total: 329

162 Game Average: 24.34

It is interesting to me that 1955 is considered to be the season where he made his greatest contribution. I would have figured 1958.

After his playing days were over Richie moved on to the broadcasting booth, where he was teamed with Harry Kalas and became the duo that called every Phillies game for the next three decades. I’ve heard other announcing teams call other games and nothing compares to Kalas and Ashburn: Kalas’s smooth voice and Ashburn’s insightful analysis made them the best announcing team in baseball. They never talked over each other and seemed to compliment each other perfectly. Ashburn called games for the Phillies until his passing in 1997. The Hall of Fame elected him in 1995, reversing its indefensible decision not to.

Where does Riche stand in terms of history? His place in Phillies history is utterly secure: his contributions for thirty-five years as the Phillies color man make him the voice of the Phillies for three generations of Phillies fans. His performance in his twelve seasons as the Phillies center fielder make him probably the most important individual position player the Phillies have ever had, aside from Mike Schmidt.

His place in the greater world of baseball is a little more complex, and I am confident that, as time goes on, Ashburn will get more of his due. Like Roberts, who hasn’t gotten his proper historical recognition because he dominated pitching in an era of explosive offense, Richie Ashburn was a great singles hitter and defensive force in an era that valued the three-run home run. According to Bill James, Ashburn’s misfortune was to be the fourth-best centerfielder of the 1950s, playing in the shadow of Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays and Duke Snider. In his Historical Abstract, James chose to rank Ashburn as one of the great center fielders in baseball history, placing him sixteenth. I think that as sabremetricians turn to defense and begin to mine defensive stats and appreciate the impact defense has had on the game, Richie Ashburn’s stature in the realm of baseball will grow. People will recognize that he was the perfect leadoff hitter and the perfect defensive center fielder. I think the future is very bright for Richie Ashburn’s memory.

James also had kind words for Ashburn’s personality and approach to the game: “Unlike [Pete] Rose, Ashburn did not extend his career beyond it natural boundaries to break any records … He didn’t need records to tell him who he was. Ashburn was a reader, a family man, a man of restraint and taste.” (The Bill James Historical Abstract at 735.) I like that quote, but I think the best words to sum up Richie Ashburn were said by Harry Kalas at Whitey’s funeral: “Why this overwhelming reaction? Because Don Richie Ashburn was Whitey: gentle and easy as a country breeze, down home, biscuits and gravy, Norman Rockwell come to life.” (Voices of Summer at 223.) I doubt that anyone could more eloquently sum up Ashburn’s life.

Tomorrow, a quick look at the Phillies free agents.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part X: The Phillies Farm System.

Part IX: The second half of the 1950 season.

Part VIII: The Braves, Cardinals, Pirates, Cubs & Reds.

Part VII: The Giants and Dodgers.

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

(4) comments

ntil 1995. It had been some thirty-three years after he stopped playing baseball before the Hall of Fame realized the tremendous mistake they had made and elected Ashburn to the Hall. Richie Ashburn is probably the most memorable player from the Wiz Kids, even more remembered than Robin Roberts.

ntil 1995. It had been some thirty-three years after he stopped playing baseball before the Hall of Fame realized the tremendous mistake they had made and elected Ashburn to the Hall. Richie Ashburn is probably the most memorable player from the Wiz Kids, even more remembered than Robin Roberts.While not a slugger like fellow 1950s centerfielders Duke Snider or Willie Mays, Richie Ashburn had a remarkable career and deserves to be remembered as one of the all-time greats. Today Ashburn would probably be an eagerly sought player for his defensive skills and talent for getting on base. In the 1950s he largely played in the shadow of Mays and Snider, much flashier players who delivered what people wanted in the 1950s: home runs. Despite Ashburn’s remarkable play in the 1950s, he was an All-Star just five times in fifteen seasons. (interestingly, Ashburn was selected to the All-Star game in both his first season and in his last.)

All Richie Ashburn did for fifteen exceptional seasons was be the most consistent table-setter in baseball, as well as be one of the best defensive players in the game. Though he never finishing higher than seventh in the MVP voting (in 1951 and 1958), Ashburn led the N.L. in On-Base Percentage (OBP) four times: 1954, 1955, 1958 & 1960. Ashburn also led the N.L. in Batting Average twice: in 1955 and 1958. He finished in the top ten in runs scored seven times, the top ten in hits nine times, and finished in the top ten in times on base for eleven seasons. Richie Ashburn as a tough out, a tenacious defender and a true gentleman. According t

o the Bill James Historical Abstract, “Richie Ashburn combined the Pete Rose virtues and the Pete Rose style of play with the virtues of dignity, intelligence and style.” (Historical Abstract, page 735.)

o the Bill James Historical Abstract, “Richie Ashburn combined the Pete Rose virtues and the Pete Rose style of play with the virtues of dignity, intelligence and style.” (Historical Abstract, page 735.)Alright, I am going to stop and give you a quick primer on the stats I will be talking about in this article, lest you be baffled about what I am talking about and quit reading:

Gross Productive Average (GPA): (1.8 * .OBP + .SLG) / 4 = .GPA. Invented by The Hardball Times Aaron Gleeman, GPA measures a players production by weighing his ability to get on base and hit with power. This is my preferred all-around stat.

Isolated Power (ISO): .SLG - .BA = .ISO. Measures a player’s raw power by subtracting singles from their slugging percentage.

On-Base Percentage (OBP): How often a player gets on base. (H + BB + HBP) / (Plate Appearances)

Slugging Percentage (SLG): Total Bases / At-Bats = Slugging Percentage. Power at the plate.

Base Runs: A stat originally created by Dave Smyth to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. Here is the formula: A: H + BB + HBP – HR; B: (.8 * 1B) + (2.1 * 2B) + (3.4 * 3B) + (1.8 * HR) + (.1*(BB + HBP)); C: AB – H; D: HR; Then simply divide B into B + C, then multiply A to the result and add D.

Runs Created (RC): A stat created by Bill James to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. Runs Created was a stat James came up with in the 1970s that revolutionized our understanding of hitting stats. The formulas for each era are different because different stats were kept track of. Prior to 1950, for example, baseball didn’t keep track of caught stealing. Here is the formula for 1950, to give you an idea about what RC measures: [(H + BB + HBP - GIDP) times (Total Bases + .26 * (BB + HBP) + .52 * Sac Hits] divided by (AB + BB + HBP + SH).

Alright, back to the story.

Richie Ashburn was born in Tilden, Nebraska, in 1927. Eagerly sought after by baseball scouts, the St. Louis Cardinals and Chicago Cubs both attempted to sign Ashburn and failed due to his young age, which prohibited him from signing any contracts. The Cleveland Indians did sign Ashburn to a contract when he was sixteen, but the deal was voided by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis and Ashburn was declared a free agent. Later the Yankees and Phillies competed for his services and Ashburn elected to sign with the Phillies in 1945 for less money ($3,500) because he seemed more likely to get to play quicker. Ashburn went to the Phillies farm club in Utica under the watchful eye of Eddie Sawyer. Originally a catcher, Sawyer wisely moved Ashburn to centerfield. It was decided that the Phillies would promote Ashburn to the team for the 1948 campaign.

Richie’s problem was that the Phillies centerfielder was Harry “The Hat” Walker, the NL batting champion for 1947. The chances of Ashburn dethroning the thirty-year old Walker seemed remote, until Walker did Ashburn a favor by deciding to hold out for more money prio

r to the 1948 season. When Walker did return to the team he was promptly injured due to his poor conditioning and soon found himself out of a job. Richie had seized the position of centerfielder and leadoff hitter and ran off with it. In his first season in the majors, Richie was a phenomenon:

r to the 1948 season. When Walker did return to the team he was promptly injured due to his poor conditioning and soon found himself out of a job. Richie had seized the position of centerfielder and leadoff hitter and ran off with it. In his first season in the majors, Richie was a phenomenon:.333 BA / .410 OBP / .400 SLG

Richie’s GPA was a tremendous .285. He created 82 runs for the Phillies in 1950, or 7.04 per 27 outs. His batting average was second in the NL to Stan Musial and his OBP was third. He had a twenty-three game hitting streak at the start of the season, then a record for rookies, and he never looked back. Harry The Hat was history.

Ashburn’s secret at the plate was his amazing bat control. Ashburn struck out in just 5% of his At-Bats in 1948. Ashburn finished his career with a 2.09 BB to K ratio. He walked 1,198 times and struck out just 571 times. He would strikeout in just 7% of his career At-Bats. He had a great eye and put the ball into play with stunning frequency. Ashburn was also fast, an asset not often prized in 1950s baseball. Ashburn frequently bunted and beat out the throws to first for hits. He also led the NL in stolen bases with 32 in 1950. Ashburn said: “A good leadoff hitter is a pain in the ass to pitchers.” (The Quotable Baseball Fanatic at 44.) Richie was a tremendous pain in the ass of opposing pitchers. Despite being sidelined for the rest of the season in August with a broken finger, Ashburn was the Rookie of the Year in 1948.

Ashburn’s family came to live in Philadelphia with him and operated a boardinghouse where teammates like Curt Simmons and Robin Roberts stayed. Ashburn struggled in 1949, partly due to what he called “swelled head”. He came back in 1950 with a terrific season, hitting .372 OBP with 91 Runs Created (5.66 per 27 outs). He terrific catch and throw in the October 1, 1950, game against the Dodgers was the great, defining moment of Ashburn’s career. (See, Part XII.)

Unfortunately, Ashburn’s sole World Series appearance was a bust. He went three-for-seventeen against the Yankees without a walk (.176 OBP). Ashburn managed just a double and two singles. He had one of the Phillies three RBIs, a sacrifice fly in the fifth inning of game two, which tied the game at 1-1. (The Phillies would go on to lose 2-1 after DiMaggio hit a home run in the top of the tenth inning.)

The next year, 1951, Ashburn had his best season since ’48, finishing second in batting average at .344 and leading the league in hits with 221. He had 118 Runs Created (101 Base Runs) and 7.07 Runs Created per 27 outs. Richie had his best year in the MVP voting in 1951, finishing seventh. He followed the 1951 campaign with a sub-par year in 1952, hitting “just” .362 OBP. At the age of just 25, Richie Ashburn was the veteran of five major league seasons:

Richie Ashburn (1948 – 1952)

Runs Created / RC27

1948: 82 / 7.04

1949: 82 / 4.55

1950: 91 / 5.66

1951: 118 / 7.07

1952: 86 / 4.93

Base Runs / BsR27

1948: 76 / 6.48

1949: 76 / 4.22

1950: 87 / 5.37

1951: 101 / 6.09

1952: 77 / 4.41

GPA:

1948: .285

1949: .242

1950: .268

1951: .283

1952: .252

From 1953 to 1958 Richie Ashburn had his most productive seasons with the Phillies. He led the NL in batting average in 1953 and 1958. He also led the NL in OBP in 1954, 1955 and 1958. Richie led the NL in walks in 1954, 1957 and 1958. Whitey was an absurdly consistent player, hitting well over the team average for On-Base-Percentage every year during this time. Each season Richie’s OBP was sixty to one hundred points over the team average. He was a machine, getting on base and playing great defense (more on that later).

Richie Ashburn (1953 – 1958)

Runs Created / RC27

1954: 113 / 7.47

1955: 120 / 8.79

1956: 105 / 6.32

1957: 99 / 5.77

1958: 135 / 8.47

Base Runs / BsR27

1954: 103 / 6.80

1955: 113 / 8.29

1956: 93 / 5.58

1957: 93 / 5.38

1958: 123 / 7.71

GPA:

1954: .292

1955: .314

1956: .269

1957: .267

1958: .308

Despite being more of a table-setter on the Phillies offense, instead of an RBI slugger like Del Ennis, Whitey was a vital part of the Phillies offense. Without him getting on base for Ennis and Granny Hammer, the Phillies would have had a punchless offense during those Wiz Kids days. To give you an idea about how vital Ashburn’s skills at getting on base were to the Wiz Kids, look at what percentage of the Phillies total Runs Created Ashburn accounted for:

1954: 16%

1955: 17%

1956: 16%

1957: 16%

1958: 18%

These are tremendous numbers when you consider that Ashburn almost never hit home runs. This was purely a product of his exceptional ability to get on base, steal bases and leg out doubles and triples.

Statistically, Ashburn’s best season was 1958. Here is a brief snapshot of that season:

Batting Average: .350 (First in N.L.)

On-Base Percentage: .440 (First in N.L.)

Slugging Percentage: .441

ISO: .091

GPA: .308

Hits: 215 (First in N.L.)

Doubles: 24

Triples: 13 (First in N.L.)

Stolen Bases: 30 (Second in N.L.)

Walks: 97 (First in N.L.)

BB/K ratio: 2.02

Total Bases: 271 (Eighth in N.L.)

In addition to making the All-Star team that season, Ashburn had his best season since 1951 in the MVP voting, once more finishing seventh. The pity was that while he was performing so well the Phillies floundered, doing no better than fourth and winning just .457 of their games during this period (398-472). Each season the Phillies never factored in the pennant race, finishing eighteen to twenty-three games out of first, which was usually occupied by the Brooklyn Dodgers. In 1958, Ashburn’s finest season, statistically, the Phils went 69-85 (.448) and finished dead-last, twenty-three games out of first place. It was the first time that the Phillies had finished in the cellar since 1947.

Richie Ashburn had a terrible campaign in 1959. His batting average crashed eighty-four points from .350 to .266. His OBP declined eighty points. His slugging percentage went down one hundred and thirty four points as well. After stealing thirty bases in forty-two attempts in 1958, Richie stole just nine in twenty tries in ’59. After hitting thirteen triples in 1958, he hit just two in 1959. Ashburn played like half the player he was. After having 135 Runs Created in 1958, Ashburn produced just 70 in 1959. He was about half as productive for the Phillies:

RC/27:

1958: 8.47

1959: 4.26

He went from being 18% of the Phillies Runs Created to 12%. The Phillies once more finished twenty-three games out of it. With Ennis gone, and Hammer, Jones, Simmons and Roberts all in decline, the Phillies were intent on cleaning house. The decision to deal Richie Ashburn was an easy one for the team, positive that his best days were long behind him.

Naturally, the Phillies were wrong. Dealt to the Cubs in January of 1960, Ashburn had a terrific season in 1960, drawing 116 walks and upping his OBP to .415 at the age of thirty-three. He regained some of the speed he lost, successfully stealing sixteen bases in twenty attempts. However, the years had taken a little wear and tear: Ashburn appeared in just ninety-nine of the Cubs 154 games. The next season he played in just forty-nine for the Cubs and out the door again.

Richie found his way to the New York Mets, the infamous 1962 expansion team that set the bar for futility with a 40-120 record. The ’62 Mets were a remarkable team, sporting two 20+ game losers (Roger Craig at 10-24, and Al Jackson at 8-20), and a lovable collection of talent-less misfits and over-the-hill veterans. Richie Ashburn was supposed to have been one of those over-the-hill vets, but he turned out to be a real gamer in 1962. At the age of thirty-five, in his fifteenth major league season, Richie Ashburn turned in a sterling performance and was selected to the 1962 NL All-Star team. Whitey’s .424 OBP was the fourth-best of his career and almost thirty points better than his career average. He also posted a career high in home runs with seven and successfully stole twelve bases in nineteen attempts. His walk-to-strikeout ratio was better than two-to-one (81 to 39). He was still a major threat. You have to shutter to think of what the Mets record would have been without Richie Ashburn.

Next I am going to direct my attention to a particular facet of Ashburn’s game: fielding. People who read this blog know that I am fascinated by fielding and consider this to be my little niche in the Phillies blogging community. Nobody talks about D like me, in part because it is such a little understood aspect of the game. My favorite quote on the subject comes, not surprisingly, from Bill James, who wrote: “Hitting is solid, pitching is liquid and defense is gaseous … damned hard to capture, formless and hard to see.”

It is hard to clearly assess Richie Ashburn’s total contribution to the Phillies defense, but it is clear to me that he was one of the best there was and his contributions are undervalued by the baseball community. Wrote Bill James: “Ashburn was regarded while active as a fine defensive center fielder, but hardly as a sensation – certainly Willie Mays was thought to be better. Ashburn’s defensive statistics, then, are the subject of unending argument among people … whom are convinced that Ashburn really was that good but the contemporary observers just overlooked him because he didn’t play in New York …” (Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame at 327.) I certainly would fall into that category. One of the things that I feel is that the Wiz Kids never got their proper historical due because they weren’t the Dodgers or the Giants (i.e., they didn’t play in one of the five boroughs of New York), and I particularly feel that Richie Ashburn’s remarkable defensive achievements are badly, badly undervalued. For the only time in my life, I would agree with George Will, who devoted two pages (276 & 277) of his 1990 book Men At Work to complain about the Hall of Fame’s decision to exclude Richie. Wrote Will: “Why is a double denied on defense so much less admirable than a double delivered on offense? … [Ashburn and the Pirates great Bill Mazeroski] may not rank with Dreyfus on the list of history’s great victims, but the undervaluing of defense does say much about the standard measures of baseball excellence. And it says much about the misunderstanding of how games are won.”

Ashburn led the N.L. in putouts every season between 1949 and 1958 but one season (1955, when he played 140 games instead of 154). Richie led the N.L. in putouts by an outfielder nine times, a record he shares with the Pirates Max Carey, who led the N.L. in 1912-1913, 1916-1918 and 1921-1924. He led the N.L. in assists three times and led the N.L. in double plays three times. In his Historical Baseball Abstract Bill James notes that Ashburn’s Fielding Percentage is better than contemporaries like Wille Mays and Mickey Mantle. James, in particular, was impressed that Ashburn made five of the top nine all-time putouts in a season, despite playing just 154 games a year. (Page 326.) However James wonders if this is partly due to the fact that Robin Roberts and the Phillies pitchers were flyball pitchers, but even so it is impressive. The National League record for putouts in a season is 547, set by the St. Louis Cardinals Taylor Douthit in 1928. Richie’s career best is 538 in 1951, just nine fewer. If Richie had played in the American League he’d be the all-time league-leader: the A.L. record is 512, set by the White Sox Chet Lemon in 1977. More specifically, Richie would occupy the #1 & #2 slots: in addition to his 538 putouts in 1951, he also notched 514 in 1949. All during these years the Phillies were one of the best defensive teams in the National League. In 1950 they were the second-best in the N.L. in terms of Defense Efficiency Ratio (DER), which measures the percentage of plays where fielders turn balls put into play into outs. Richie was the major reason why they were so good for so long. Little surprise then that the season after Richie left to join the Cubs the Phillies fell to dead-last in DER. I think Ashburn’s effect on the Phillies is best summed up by temmate Robin Roberts: “I was fortunate as a pitcher. I had terrific defensive players behind me … the best of all was Richie [Ashburn]. I can’t tell you how many games I won with his glove and speed.” (Legends of the Phillies, page 16.)

Here are Richie’s putouts and assists season-by-season:

Put-Outs / Assists

1948: 344 / 14

1949: 514 / 13

1950: 405 / 8

1951: 538 / 15

1952: 428 / 23

1953: 496 / 18

1954: 483 / 12

1955: 387 / 10

1956: 503 / 11

1957: 502 / 18

1958: 495 / 8

1959: 359 / 4

1960: 317 / 11

1961: 131 / 4

1962: 187 / 9

Career: 6,084 / 174

According to James, after his injured his arm in 1951 Ashburn’s throws were slower and less powerful. However, Ashburn “compensated with quickness and positioning, and led the league in baserunner kills in 1952, 1953 and 1957.” (The Bill James Historical Abstract at 734.) I think that fact is a powerful argument for Ashburn’s greatness as well: he was quick and fast and very, very smart.

The single play that Richie Ashburn is most known for, of course, is his throw in the bottom on the ninth of the final game of the 1950 season against the Dodgers. I’ll discuss it a little more in Part XII, but the basic facts were that the Dodgers and Phillies were tied at 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth inning. If the Dodgers won, they’d force a playoff series with the ragged Phillies, who entered the game with a five game losing streak. With runners on first and second and no outs, Duke Snider got a hit right up the middle of the field. The Dodgers waved home Cal Abrams, who was rounding third from second base, while Richie Ashburn, who was playing shallow, moved in, scooped up the ball and hurled it to home, where catcher Stan Lopata tagged Abrams out by fifteen feet. Instead of winning the game 2-1 and forcing the playoff series, the Dodgers ended up failing to score a run and losing the game on Dick Sisler’s three-run home run in the top of the tenth inning. Ashburn’s quick reflexes and quick throw saved the Phillies the pennant.

It was such a tremendous play, such a tremendous moment, that Bill James felt it would have been one of the great moments in baseball history, had it not been for the fact that the very next season Bobby Thomson hit the climatic home run against the Dodgers to cap the ’51 playoffs, this game and Ashburn’s throw might be immortalized as one of the great moments in the history of the game. Certainly, had Thomson not obliterated the memory of the '50 pennant race, it would have sped Ashburn’s ascent to the Hall of Fame. And how appropriate that Ashburn’s greatest play was a defensive one?

For my post on Robin Roberts I gave an overview of his career via win shares by season. I’ll do the same for Richie:

Win Shares:

1948: 21

1949: 19

1950: 23

1951: 28

1952: 21

1953: 26

1954: 26

1955: 29

1956: 28

1957: 26

1958: 28

1959: 14

1960: 22

1961: 6

1962: 11

Career Total: 329

162 Game Average: 24.34

It is interesting to me that 1955 is considered to be the season where he made his greatest contribution. I would have figured 1958.

After his playing days were over Richie moved on to the broadcasting booth, where he was teamed with Harry Kalas and became the duo that called every Phillies game for the next three decades. I’ve heard other announcing teams call other games and nothing compares to Kalas and Ashburn: Kalas’s smooth voice and Ashburn’s insightful analysis made them the best announcing team in baseball. They never talked over each other and seemed to compliment each other perfectly. Ashburn called games for the Phillies until his passing in 1997. The Hall of Fame elected him in 1995, reversing its indefensible decision not to.

Where does Riche stand in terms of history? His place in Phillies history is utterly secure: his contributions for thirty-five years as the Phillies color man make him the voice of the Phillies for three generations of Phillies fans. His performance in his twelve seasons as the Phillies center fielder make him probably the most important individual position player the Phillies have ever had, aside from Mike Schmidt.

His place in the greater world of baseball is a little more complex, and I am confident that, as time goes on, Ashburn will get more of his due. Like Roberts, who hasn’t gotten his proper historical recognition because he dominated pitching in an era of explosive offense, Richie Ashburn was a great singles hitter and defensive force in an era that valued the three-run home run. According to Bill James, Ashburn’s misfortune was to be the fourth-best centerfielder of the 1950s, playing in the shadow of Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays and Duke Snider. In his Historical Abstract, James chose to rank Ashburn as one of the great center fielders in baseball history, placing him sixteenth. I think that as sabremetricians turn to defense and begin to mine defensive stats and appreciate the impact defense has had on the game, Richie Ashburn’s stature in the realm of baseball will grow. People will recognize that he was the perfect leadoff hitter and the perfect defensive center fielder. I think the future is very bright for Richie Ashburn’s memory.

James also had kind words for Ashburn’s personality and approach to the game: “Unlike [Pete] Rose, Ashburn did not extend his career beyond it natural boundaries to break any records … He didn’t need records to tell him who he was. Ashburn was a reader, a family man, a man of restraint and taste.” (The Bill James Historical Abstract at 735.) I like that quote, but I think the best words to sum up Richie Ashburn were said by Harry Kalas at Whitey’s funeral: “Why this overwhelming reaction? Because Don Richie Ashburn was Whitey: gentle and easy as a country breeze, down home, biscuits and gravy, Norman Rockwell come to life.” (Voices of Summer at 223.) I doubt that anyone could more eloquently sum up Ashburn’s life.

Tomorrow, a quick look at the Phillies free agents.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part X: The Phillies Farm System.

Part IX: The second half of the 1950 season.

Part VIII: The Braves, Cardinals, Pirates, Cubs & Reds.

Part VII: The Giants and Dodgers.

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

The Wiz Kids, Part X: Focus on the Farm System

I thought I might focus, briefly, on the development system that gave birth to the Wiz Kids, the Phillies farm system of the 1940s.

As many people are aware, the elaborate farm system, the minor leagues, that support the thirty MLB franchises by developing and nurturing players is fairly unique to professional sports. The NFL doesn’t have such a system, although some teams dump players on the NFL Europe for experience, relying instead on college to train and equip players for the rigors of the NFL season. The NBA likewise does the same. Hockey has a farm system for developing players, but it isn’t quite as elaborate or well-defined as the MLB and rookies oftentimes go from amateur status to the pros very quickly.

many people are aware, the elaborate farm system, the minor leagues, that support the thirty MLB franchises by developing and nurturing players is fairly unique to professional sports. The NFL doesn’t have such a system, although some teams dump players on the NFL Europe for experience, relying instead on college to train and equip players for the rigors of the NFL season. The NBA likewise does the same. Hockey has a farm system for developing players, but it isn’t quite as elaborate or well-defined as the MLB and rookies oftentimes go from amateur status to the pros very quickly.

The farm system began largely by Cardinals General Manager Branch Rickey, the genius who shattered the color barrier in 1947 by bringing Jackie Robinson to the National League with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey, the G.M. of the Cardinals in the Roaring Twenties and the Depression-Era Thirties, took minor league teams and utilized them as a training ground for emerging Cardinals stars. Prior to Rickey, minor league teams had loose alliances with MLB teams and earned most of their money by selling stars to big league teams.

Rickey turned that all on its head by stashing talented players on minor league affiliates to groom them and prepare them for professional baseball. The Cardinals success under Rickey convinced teams like the New York Yankees to counter with their own farm system, which soon led other teams to follow suit. By the mid-1940s, nearly every team in the majors had a farm system. The Phillies were forced to follow suit under the leadership of General Manager Herb Pennock.

Pennock, who a ctually holds the distinction of being the Phillies first General Manager, was hired in 1943 when Robert Carpenter, Jr., the team’s new (and young) President, was drafted into the Army to serve in World War II. Carpenter turned operations traditionally conducted by the team President over to Pennock. At the time Pennock took over the Phillies had a meager relationship with a minor league team in Trenton and had just one scout. Pennock and Carpenter formulated a five year plan to return the Phillies to respectability. The cornerstone of their strategy was to expand the Phillies farm system and develop talent internally.

ctually holds the distinction of being the Phillies first General Manager, was hired in 1943 when Robert Carpenter, Jr., the team’s new (and young) President, was drafted into the Army to serve in World War II. Carpenter turned operations traditionally conducted by the team President over to Pennock. At the time Pennock took over the Phillies had a meager relationship with a minor league team in Trenton and had just one scout. Pennock and Carpenter formulated a five year plan to return the Phillies to respectability. The cornerstone of their strategy was to expand the Phillies farm system and develop talent internally.

In the ensuing seasons the Phillies dramatically improved. First they shed their old roster. The only player who remained on the 1947 team from the previous regime’s squad in 1943 was catcher Andy Seminick (who actually joined the Phillies that season). Pennock expanded the Phillies minor league network from one team to eleven and hired eight more scouts to give the team a total of nine. Carpenter, a wealthy businessman and a distant member of the du Pont family, wasn’t afraid to spend money and handed out signing bonuses, including $25,000 for Robin Roberts and $65,000 for Curt Simmons. Between 1944 and 1948 the Phillies spent $1.25 million dollars in signing bonuses, quite a turn-around from a team that had been skinflints until then.

The farm system actually developed the Wiz Kids much more rapidly than expected. The 1950 team hadn’t been expected to compete under the team’s Five Year Plan until 1951 or 1952. It is remarkable how successful the Phillies farm system, and principally its affiliate in Toronto, which had been led by future Manager Eddie Sawyer, had been in developing talent for the Phillies. Of the eight everyday regulars on the Wiz Kids roster just one – Seminick – predated the Pennock / Carpenter regime and of those seven, five were developed by the Phillies farm system: Outfielders Richie Ashburn and Del Ennis, as well as second baseman Mike Goliat, third baseman Willie Jones and shortstop Granny Hamner. Outfielder Dick Sisler and first baseman Eddie Waitkus were acquired in trades in 1948. Backup catcher Stan Lopata and reserve outfielder Jackie Mayo were also players signed by the team and brought up via the farm system.

Willie Jones and shortstop Granny Hamner. Outfielder Dick Sisler and first baseman Eddie Waitkus were acquired in trades in 1948. Backup catcher Stan Lopata and reserve outfielder Jackie Mayo were also players signed by the team and brought up via the farm system.

In addition to Roberts and Simmons, the Phillies also developed pitcher Bob Miller, the team’s third starter in 1950, on the farm along with Bubba Church. Of the six pitchers who constituted the Phillies starting rotation in 1950, just two – Ken Heintzelman and Russ Meyer – were acquired from other teams.

Jim Konstanty is a special case – a player acquired as a cast-off from a rival organization, specifically the Boston Braves – and brought to Toronto to develop his skills before being brought to Philadelphia. But here again, the Phillies farm system laid the groundwork for Konstanty’s MVP season in 1950. Konstanty has to be seen as a product of the farm system that Pennock and Carpenter built in the 1940’s.

Here are the dates when the critical parts of the Wiz Kids came together:

1943

Andy Seminick – traded from Pittsburgh Pirates

Del Ennis – signed as a free agent

1944

Granny Hamner – signed as a free agent

1945

Richie Ashburn – signed as a free agent

1946

Stan Lopata – signed as a free agent

1947

Curt Simmons – signed as a free agent

Mike Goliat – signed as a free agent

Willie Jones – signed as a free agent

Bubba Church – signed as a free agent

Jackie Mayo – signed as a free agent

Ken Heintzelman – purchased from Pittsburgh Pirates for cash

1948

Robin Roberts – signed as a free agent

Bob Miller – signed as a free agent

Russ Meyer – bought from Chicago Cubs for cash

Dick Sisler – traded from St. Louis Cardinals

Eddie Waitkus – traded from Chicago Cubs

This was an almost entirely home-grown operation, which goes to show the wisdom of developing a vast, deep minor league operation to develop and produce quality players.

Unfortunately for Herb Pennock, he passed away in 1948, two years before the Wiz Kids would take the field. The team was run from 1948 to 1953 by Carpenter. As you can see, the team turned unlucky in the years after Pennock in terms of developing talent. Unwilling to bring in African-American players, the Wiz Kids quickly atrophied as a team. Carpenter’s eye wasn’t as savvy as former big leaguer Pennock and the team failed to sign players to succeed the Wiz Kids as they grew older. Carpenter and the Phillies failed to sign a black player until 1957, a full decade after Jackie Robinson shattered the color barrier, costin g the Phillies the opportunity to sign players like Roy Campanella and Hank Aaron. While it is tempting to assign the blame for the team’s reluctance to sign black players on Carpenter, it must be noted that Pennock was a virulent racist who attempted to intimidate Branch Rickey from bringing Jackie Robinson to Philadelphia for a regular season game in 1947. The racial issues that plagued the Phillies in the 1950s and 1960s stem from the otherwise brilliant Herb Pennock’s stewardship of the team.

g the Phillies the opportunity to sign players like Roy Campanella and Hank Aaron. While it is tempting to assign the blame for the team’s reluctance to sign black players on Carpenter, it must be noted that Pennock was a virulent racist who attempted to intimidate Branch Rickey from bringing Jackie Robinson to Philadelphia for a regular season game in 1947. The racial issues that plagued the Phillies in the 1950s and 1960s stem from the otherwise brilliant Herb Pennock’s stewardship of the team.

Roy Hamey took over as General Manager from 1954 through 1959 and attempted to rebuild the Wiz Kids via trades, but ended up frittering the last bits of talent that remained from the ’50 team away until he was replaced in 1959 by John Quinn, the man who would build the ’64 team and then pry Steve Carlton away from the Cardinals. Carpenter would remain the Phillies President until 1972, when he retired and was replaced by his son, who helped oversee the team’s sole World Series triumph.

Associated Reading: check out this (click for Part I, click for Part II, and click for Part III) excellant series written by The Hardball Times Steve Treder concerning the farm system from 1946 to 1960. Treder talks a little about the Wiz Kids, although his primary area of focus is on the Yankees and Cardinals.

Tomorrow, Richie Ashburn. Friday, we will talk a little about the free agency market.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part IX: The second half of the 1950 season.

Part VIII: The Braves, Cardinals, Pirates, Cubs & Reds.

Part VII: The Giants and Dodgers.

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

(0) comments

As

many people are aware, the elaborate farm system, the minor leagues, that support the thirty MLB franchises by developing and nurturing players is fairly unique to professional sports. The NFL doesn’t have such a system, although some teams dump players on the NFL Europe for experience, relying instead on college to train and equip players for the rigors of the NFL season. The NBA likewise does the same. Hockey has a farm system for developing players, but it isn’t quite as elaborate or well-defined as the MLB and rookies oftentimes go from amateur status to the pros very quickly.

many people are aware, the elaborate farm system, the minor leagues, that support the thirty MLB franchises by developing and nurturing players is fairly unique to professional sports. The NFL doesn’t have such a system, although some teams dump players on the NFL Europe for experience, relying instead on college to train and equip players for the rigors of the NFL season. The NBA likewise does the same. Hockey has a farm system for developing players, but it isn’t quite as elaborate or well-defined as the MLB and rookies oftentimes go from amateur status to the pros very quickly.The farm system began largely by Cardinals General Manager Branch Rickey, the genius who shattered the color barrier in 1947 by bringing Jackie Robinson to the National League with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey, the G.M. of the Cardinals in the Roaring Twenties and the Depression-Era Thirties, took minor league teams and utilized them as a training ground for emerging Cardinals stars. Prior to Rickey, minor league teams had loose alliances with MLB teams and earned most of their money by selling stars to big league teams.

Rickey turned that all on its head by stashing talented players on minor league affiliates to groom them and prepare them for professional baseball. The Cardinals success under Rickey convinced teams like the New York Yankees to counter with their own farm system, which soon led other teams to follow suit. By the mid-1940s, nearly every team in the majors had a farm system. The Phillies were forced to follow suit under the leadership of General Manager Herb Pennock.

Pennock, who a

ctually holds the distinction of being the Phillies first General Manager, was hired in 1943 when Robert Carpenter, Jr., the team’s new (and young) President, was drafted into the Army to serve in World War II. Carpenter turned operations traditionally conducted by the team President over to Pennock. At the time Pennock took over the Phillies had a meager relationship with a minor league team in Trenton and had just one scout. Pennock and Carpenter formulated a five year plan to return the Phillies to respectability. The cornerstone of their strategy was to expand the Phillies farm system and develop talent internally.

ctually holds the distinction of being the Phillies first General Manager, was hired in 1943 when Robert Carpenter, Jr., the team’s new (and young) President, was drafted into the Army to serve in World War II. Carpenter turned operations traditionally conducted by the team President over to Pennock. At the time Pennock took over the Phillies had a meager relationship with a minor league team in Trenton and had just one scout. Pennock and Carpenter formulated a five year plan to return the Phillies to respectability. The cornerstone of their strategy was to expand the Phillies farm system and develop talent internally.In the ensuing seasons the Phillies dramatically improved. First they shed their old roster. The only player who remained on the 1947 team from the previous regime’s squad in 1943 was catcher Andy Seminick (who actually joined the Phillies that season). Pennock expanded the Phillies minor league network from one team to eleven and hired eight more scouts to give the team a total of nine. Carpenter, a wealthy businessman and a distant member of the du Pont family, wasn’t afraid to spend money and handed out signing bonuses, including $25,000 for Robin Roberts and $65,000 for Curt Simmons. Between 1944 and 1948 the Phillies spent $1.25 million dollars in signing bonuses, quite a turn-around from a team that had been skinflints until then.

The farm system actually developed the Wiz Kids much more rapidly than expected. The 1950 team hadn’t been expected to compete under the team’s Five Year Plan until 1951 or 1952. It is remarkable how successful the Phillies farm system, and principally its affiliate in Toronto, which had been led by future Manager Eddie Sawyer, had been in developing talent for the Phillies. Of the eight everyday regulars on the Wiz Kids roster just one – Seminick – predated the Pennock / Carpenter regime and of those seven, five were developed by the Phillies farm system: Outfielders Richie Ashburn and Del Ennis, as well as second baseman Mike Goliat, third baseman

Willie Jones and shortstop Granny Hamner. Outfielder Dick Sisler and first baseman Eddie Waitkus were acquired in trades in 1948. Backup catcher Stan Lopata and reserve outfielder Jackie Mayo were also players signed by the team and brought up via the farm system.

Willie Jones and shortstop Granny Hamner. Outfielder Dick Sisler and first baseman Eddie Waitkus were acquired in trades in 1948. Backup catcher Stan Lopata and reserve outfielder Jackie Mayo were also players signed by the team and brought up via the farm system.In addition to Roberts and Simmons, the Phillies also developed pitcher Bob Miller, the team’s third starter in 1950, on the farm along with Bubba Church. Of the six pitchers who constituted the Phillies starting rotation in 1950, just two – Ken Heintzelman and Russ Meyer – were acquired from other teams.

Jim Konstanty is a special case – a player acquired as a cast-off from a rival organization, specifically the Boston Braves – and brought to Toronto to develop his skills before being brought to Philadelphia. But here again, the Phillies farm system laid the groundwork for Konstanty’s MVP season in 1950. Konstanty has to be seen as a product of the farm system that Pennock and Carpenter built in the 1940’s.

Here are the dates when the critical parts of the Wiz Kids came together:

1943

Andy Seminick – traded from Pittsburgh Pirates

Del Ennis – signed as a free agent

1944

Granny Hamner – signed as a free agent

1945

Richie Ashburn – signed as a free agent

1946

Stan Lopata – signed as a free agent

1947

Curt Simmons – signed as a free agent

Mike Goliat – signed as a free agent

Willie Jones – signed as a free agent

Bubba Church – signed as a free agent

Jackie Mayo – signed as a free agent

Ken Heintzelman – purchased from Pittsburgh Pirates for cash

1948

Robin Roberts – signed as a free agent

Bob Miller – signed as a free agent

Russ Meyer – bought from Chicago Cubs for cash

Dick Sisler – traded from St. Louis Cardinals

Eddie Waitkus – traded from Chicago Cubs

This was an almost entirely home-grown operation, which goes to show the wisdom of developing a vast, deep minor league operation to develop and produce quality players.

Unfortunately for Herb Pennock, he passed away in 1948, two years before the Wiz Kids would take the field. The team was run from 1948 to 1953 by Carpenter. As you can see, the team turned unlucky in the years after Pennock in terms of developing talent. Unwilling to bring in African-American players, the Wiz Kids quickly atrophied as a team. Carpenter’s eye wasn’t as savvy as former big leaguer Pennock and the team failed to sign players to succeed the Wiz Kids as they grew older. Carpenter and the Phillies failed to sign a black player until 1957, a full decade after Jackie Robinson shattered the color barrier, costin

g the Phillies the opportunity to sign players like Roy Campanella and Hank Aaron. While it is tempting to assign the blame for the team’s reluctance to sign black players on Carpenter, it must be noted that Pennock was a virulent racist who attempted to intimidate Branch Rickey from bringing Jackie Robinson to Philadelphia for a regular season game in 1947. The racial issues that plagued the Phillies in the 1950s and 1960s stem from the otherwise brilliant Herb Pennock’s stewardship of the team.

g the Phillies the opportunity to sign players like Roy Campanella and Hank Aaron. While it is tempting to assign the blame for the team’s reluctance to sign black players on Carpenter, it must be noted that Pennock was a virulent racist who attempted to intimidate Branch Rickey from bringing Jackie Robinson to Philadelphia for a regular season game in 1947. The racial issues that plagued the Phillies in the 1950s and 1960s stem from the otherwise brilliant Herb Pennock’s stewardship of the team.Roy Hamey took over as General Manager from 1954 through 1959 and attempted to rebuild the Wiz Kids via trades, but ended up frittering the last bits of talent that remained from the ’50 team away until he was replaced in 1959 by John Quinn, the man who would build the ’64 team and then pry Steve Carlton away from the Cardinals. Carpenter would remain the Phillies President until 1972, when he retired and was replaced by his son, who helped oversee the team’s sole World Series triumph.

Associated Reading: check out this (click for Part I, click for Part II, and click for Part III) excellant series written by The Hardball Times Steve Treder concerning the farm system from 1946 to 1960. Treder talks a little about the Wiz Kids, although his primary area of focus is on the Yankees and Cardinals.

Tomorrow, Richie Ashburn. Friday, we will talk a little about the free agency market.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part IX: The second half of the 1950 season.

Part VIII: The Braves, Cardinals, Pirates, Cubs & Reds.

Part VII: The Giants and Dodgers.

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.