Friday, October 27, 2006

The Wiz Kids, Part VIII: Focus on the Opposition … the also-rans.

I’ve complained often that the media is obsessed with the City of New York. How many TV shows are set in New York City? Everything that happens in New York is news because the national media is headquartered there and thinks that the world begins and ends at the edge of Manhattan Island. History’s obsession with New York baseball reached its nadir in the 1950s when the Dodgers, Giants and Yankees had their way with the rest of the major leagues and culminated with a dramatic series of events: Bobby Thomson’s home run in 1951, the Dodgers winning the 1955 World Series, Don Larsen’s perfect game in 1956, and the decision by the Giants and Dodgers to leave New York for California in 1957. So the obsession the media has with New York baseball in the 1950s is understandable, but very frustrating. Of the sixteen major league teams, thirteen played outside of the confines of New York City.

Well, the Dodgers and Giants weren’t the only teams competing with the Phillies for the National League pennant. To varying degrees the Boston Braves and St. Louis Cardinals were also in the thick of things in the NL pennant race, while fans in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Chicago dreamed of better days ahead. Let’s look at them, starting with the Braves.

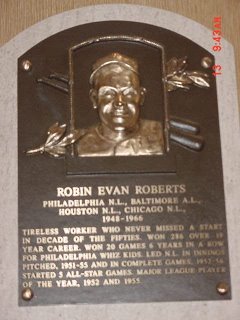

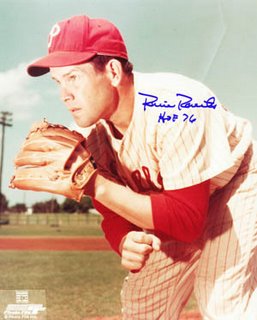

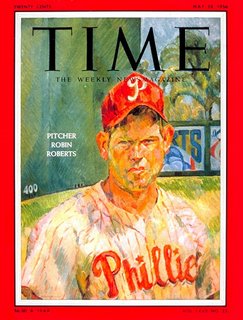

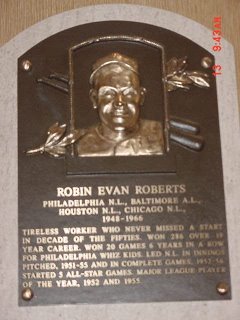

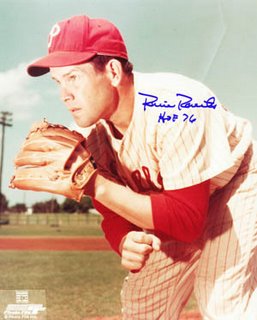

The Boston Braves. I realized something about the 1950 Boston Braves as I examined their stats. This team had a very good pitching staff. Very good. Jim Konstanty may have won the 1950 MVP award, and Robin Roberts may generally be recognized for being the best pitcher in the NL in 1950, but there is an argument to be made that Warren Spahn was the best pitcher in the NL in 1950. Look at FIP ERAs*:

Jim Konstanty: 3.70

Robin Roberts: 3.55

Curt Simmons: 3.53

Warren Spahn: 3.32

* FIP – Fielding Independent Pitching: (13*HR+3*BB-2*K / IP) + League Factor Evaluates a pitching by how he would have done with an average defense behind him by keeping track of things that a pitcher can control (walks, strikeouts, home runs allowed) as opposed to things he cannot (hits allowed, runs allowed).

This was an extraordinarily talented team that boasted a tremendous threesome of Spahn, Johnny Sain and Vern Bickford. Spahn, Sain and Bickford threw 883 of the Braves 1,385 innings (64%) that season. Aside from Roberts 304 and a third innings, nobody threw more innings then Bickford (311 & 2/3), Spahn (293) and Sain (278 & 1/3) in the NL. They went 60-44 and threw 77 complete games. They were an extraordinary trio, but they were all the team had. Their collective ERA was 3.52. The rest of the team was 5.24 …

The Braves also had a good offense, finishing second in the NL in runs scored with 785, 63 more than the Phillies. The Braves were third in the NL in Isolated Power at .142, compared to the Phils .134, and second in Gross Productive Average (GPA) at .253, as compared to the Phillies .248 … The Braves had a very efficient offensive unit. Their 785 runs dramatically out-performs their Base Runs (734), their Batting Runs (746) and their Runs Created (761).

Confused about what I’m talking about? Here are the stats I refer to defined:

Gross Productive Average (GPA): (1.8 * .OBP + .SLG) / 4 = .GPA. Invented by The Hardball Times Aaron Gleeman, GPA measures a players production by weighing his ability to get on base and hit with power. This is my preferred all-around stat.

Isolated Power (ISO): .SLG - .BA = .ISO. Measures a player’s raw power by subtracting singles from their slugging percentage.

On-Base Percentage (OBP): How often a player gets on base. (H + BB + HBP) / (Plate Appearances)

Walks per plate appearance (BB/PA): BB / PA = .BB/PA Avg

Slugging Percentage (SLG): Total Bases / At-Bats = Slugging Percentage. Power at the plate.

Runs Created (RC): A stat originally created by Bill James to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. The formula I use for this article is taken from Bill James Historical Abstract circa 1988, when he developed special formulas for Runs Created based on stats that the MLB kept (e.g., caught stealing wasn't a stat baseball kept track of until 1951). The formula is: [(H + BB + HBP - GIDP) times (Total Bases + .26 * (BB + HBP) + .52 * SH)] divided by (AB + BB + HBP + SH).

RC/27: Runs Created per 27 outs, essentially what a team of 9 of this player would score in a hypothetical game.

Base Runs: Developed by Dave Smyth as an alternative to Runs Created. Here is the formula: (A: H + BB + HBP – HR ; B: (.8 * 1B) + (2.1 * 2B) + (3.4 * 3B) + (1.8 * HR) + (.1*(BB + HBP)); C: AB – H; D: HR) Then simply divide B into B + C, then multiply A to the result and add D.

Batting Runs: Another alternative to Runs Created, developed by Pete Palmer as part of his linear weights system. The formula: (.47 * H) + (.38 * D) + (.55 * T) + (.93 * HR) + (.33 * (BB + HBP)) + (.22 * SB) + (-.38 * CS) + (-.10 * (AB - H)).

The key to the Braves offense was balance. They had five players who hit fourteen or more home runs. The team did not merely rely on Earl Torgeson (123 Runs Created, 7.81 Runs Created per 27 Outs, 114 Base Runs), Sid Gordon (107 Runs Created, 8.27 Runs Created per 27 Outs, 103 Base Runs) and Bob Elliott (103 Runs Created, 7.19 Runs Created per 27 Outs, 99 Base Runs), they also had NL Rookie of the Year Sam Jethroe, who led the NL in stolen bases with thirty-five (twice as many as the Dodgers Pee Wee Reese). The Braves were the second-best offensive team in the NL after the Dodgers. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough.

On May 6 the Braves were in first place with a 10-7 record, and they would steadily hang in the playoff picture for another two months. At the All-Star break the Braves were 42-31, two games behind the Phillies. After defeating the Chicago Cubs 10-2 on August 4 behind Warrn Spahn, the Braves were three games out of first and very much in the thick of the playoff hunt. The Braves then lost ten of their next fourteen games and tumbled to eight games out. The Braves would battle back to try and keep pace with the Phillies, but it was too much. On September 17, 1950, they managed to jump into second place, a half game ahead of the Dodgers and seven and a half behind the Phillies, but the Braves would go 5-11 the rest of the way, while the Dodgers made a 13-5 dash to catch up to the Phillies. I suspect that if you go back and examine the Braves season, you’ll find that the strain of pitching every third day wore Spahn, Bickford and Sain down.

The Braves would leave the Boston area after the 1952 season and journey westward to Milwaukee, where they immediately became the prime challenger to the Dodgers – Giants duopoly, finishing second to the Dodgers in 1953, 1955 and 1956 before breaking through to win the 1957 World Series over the Yankees and grab the ’58 pennant as well. The Braves deserted Milwaukee in 1965 and journeyed to the South to Atlanta, where they became baseball’s sole team inside of the Old Confederacy (excluding Texas) until the Florida Marlins were created in 1993. Until the team’s modern era (since 1990), the Atlanta Braves were an also-ran for nearly three decades.

The St. Louis Cardinals. Back in the 1950s, the St. Louis Cardinals were the extreme western limit of major league baseball. It was simply too far for teams to travel in trains to go that much further west of the Mississippi River. Air travel, which became widely available during the ‘50s, enabled baseball to move west and embrace California and the Mountain West. However until the A’s abandoned Philadelphia for Kansas City in 1955, the Cardinals were baseball’s western team and the southern team as well.

The Cardinals had a lot of proud history going into the 1950 season. They had most recently won the World Series in 1946, defeating the Boston Red Sox in seven games. Prior to 1946, they had captured the NL pennant in 1942, 1943 and 1944, winning the series in ’42 over the Yankees and in ’44 over the cross-town Browns (who would later move to Baltimore and go on to become the Orioles). Even before that the Cardinals had the Gashouse Gang, a goofy collection of players who had captured the NL pennant five times in nine years between 1926 and 1934 and won three World Series.

The 1950 Cardinals would be less fortunate than their 1920s, 1930s and 1940s counterparts. The ‘50’s weren’t a good time for the Cards. 1946 would turn out to be Stan Musial’s last championship. The Cards wouldn’t capture the NL pennant again until 1964, when the Phillies aided their path to the World Series by collapsing at the end of the season.

Jim Konstanty won the 1950 MVP award and was unquestionably vital to the Phillies in their battle for the post-season, however, I think the best individual player in the league in 1950 was the Cardinals Musial. The twenty-time All-Star had won the MVP award in 1943, 1946 and 1948, and finished second to Konstanty in 1950. Musial would be the NL runner-up from 1949 to 1951.

Musial was a phenomenal player. He may not have had the most explosive bat in the league, but he was consistently the most dangerous hitter.

NL Runs Created (1950):

1. Musial (Cards): 149

2. Snider (Dodgers): 133

3. Kiner (Pirates): 130

4. Torgeson (Braves): 123

5. Stanky (Giants): 121

6. Pafko (Cubs): 121

Musial produced 10.75 runs created per 27 outs, tops in the league. That only gives you a brief glimpse at how tough an out Musial was.

Unfortunately for Musial, the Cardinals didn’t have a whole lot else going for them. The rest of the team had aged and atrophied over the three years since the Cards won the World Series. The Cardinals had a decent pitching staff, which finished second to the Phillies in the league in Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), and home runs allowed (0.79 per nine innings, as well as third in league in walks allowed (3.55 per nine innings), and strikeouts (4.00 per nine innings). The Cards didn’t have a lot of pop at the plate after Musial and they didn’t play defense well. As late in the season as July 20, after sweeping both ends of a double-header with 18-4 and 10-3 victories, the Cardinals owned sole possession of first place in the NL. After that, the Cardinals would drop 41 of their remaining 71 games and struggle to remain at .500. The season would end with the Cardinals in fifth place.

The Cincinnati Reds. There wasn’t a whole lot positive for Reds fans in 1950. The team finished sixth, a position it would occupy for the next three seasons as well. The Phillies largely had their way with the Reds in 1950, winning eighteen of their twenty-two games against them, easily the Phillies best performance against any other team in the National League that season.

The Reds did little right in 1950. They finished dead-last in the NL in Isolated Power (ISO) at .116, well under the league average of .140 and the Phillies .131 … The Reds Gross Productive Average (GPA) was nearly the worst as well, at .240, as compared with the NL average of .250 and the Phillies .248. The Reds were last in the NL in BaseRuns with 631, last in the NL in Batting Runs with 638, and last in the NL in Runs Created with 652. They were the second-worst scoring offense in the NL.

Their pitching wasn’t much better, finishing seventh in the NL in ERA, fifth in FIP ERA, seventh in walks allowed (3.86 per nine innings) and sixth in home runs allowed (0.96 per nine innings). The only areas where the Reds excelled at were defense, where the Reds had the third-best DER in the NL – .708 – after the Phillies (.719) and Giants (.729), and strikeouts, where the Reds pitching staff K’d 4.55 batters per nine innings, a terrific number only exceeded by the Dodgers (5.00).

A disastrous May (6-19) saw the Reds occupy the cellar for most of the season. After losing to the Dodgers 8-2 on June 20, the Reds were in dead-last, 15-38 (.283), a whopping eighteen games behind the Dodgers and seventeen behind the Phillies and Cardinals just fifty-three games into the season. The Reds went on to win as many games as they lost the rest of the way (51-49), but the damage was done. A ten-game losing streak from August 18 to August 27 ended any chance the Reds had of a winning season. They limped to a sixth place finish. Their 28-49 record at home (.364, versus 38-38, .500 on the road) kept fans away in droves. The Reds drew 538,794 fans in 1950, nearly 405,597 fewer fans than the Braves, the next-worst team in terms of attendance. The Pirates and Cubs, despite finishing worse than the Reds, attracted well over twice as many fans to their ballparks.

The Pittsburgh Pirates. The 1950 Pirates were an interesting enigma, though they were the worst team in the NL, a distinction they would possess or share until 1958, when they finished in second place and get ready to play in the 1960 World Series. The Pirates would finish seventh or eighth every year from 1950 to 1957, despite having future Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner in the lineup.

Kiner was a remarkable player: just 27 entering the 1950 season, he had hit 54 home runs in 1949 and entered the 1950 season having hit 168 home runs already in his brief career. He hit another 47 in 1950 and drove in 118 runs. Kiner may have been the best hitter in the NL in 1950 (though I think that distinction belongs to Stan Musial), and his presence in the lineup helped the Pirates finish second in Isolated Power and Slugging Percentage and third in Gross Productive Average in the NL. And yet the Pirates were sixth in runs scored. On paper they should have been a pretty decent team at the plate, but no team had a bigger variance between its Runs Created and Actual Runs:

Runs Created / Actual Runs

Reds: 652 / 681 (+29)

Braves: 761 / 785 (+24)

Cubs: 643 / 658 (+15)

Dodgers: 841 / 847 (+6)

Giants: 738 / 735 (-3)

Phillies: 725 / 722 (-3)

Cardinals: 701 / 693 (-8)

Pirates: 737 / 681 (-56)

The Pirates problem simply was that Kiner was their only real threat. Note that 40% of Kiner’s RBIs were of himself: home runs. Kiner drove in just 71 teammates. Compare that to Duke Snider, whose home runs amount to just 30% of his RBIs, or Del Ennis, whose homers were 25% of his RBIs. Kiner had 130 Runs Created in 1950, 18% of the team’s output. Bill James noted that the ’50 Pirates were the most inefficient team of the 1950s in his 2005 Handbook (Page 15), losing fourteen more games than they should have. It was an offensively inefficient team and you have to wonder how frustrated Kiner was playing on the Pirates.

Defensively the Pirates were pretty ordinary. In terms of pitching the Pirates were the worst in the NL: dead-last in terms of ERA (in fact over a half run worse than the next-worst team, the Cincinnati Reds) and dead-last in terms of FIP (a quarter of a run worse than the Cubs). No team got fewer strikeouts (3.66 per nine innings), surrendered more walks (4.05 per nine innings), and only the Dodgers gave up more home runs (1.00 per nine innings).

Interestingly, despite being the worst team in the National League and never really being a factor in the race for the pennant (even as early as June 1, 1950, the Pirates were eight games out of first), the Pirates were third in the NL in attendance, after the Phillies and Dodgers. In fact the Pirates drew just 19,629 fewer people than the Dodgers and 50,768 fewer than the Phillies. The Pirates drew more than twice as many fans as their rivals down the Ohio River, the Cincinnati Reds. Despite being a bad team, they were popular.

The Chicago Cubs. I’ve always thought that the Chicago Cubs are a very strange franchise. Whereas the suffering of the Boston Red Sox inspired Shakespearean pathos thanks to the multitudes of writers who live in or hail from New England, the Cubs have a sort of bland Midwestern happiness to their futility. The Red Sox may have been cursed to fail as spectacularly as they have, but the Cubs are the victims of simple incompetence.

The 1950 Cubs were nothing special, and have no indication to their fans that they had played in the 1945 World Series and nearly won. Their offense was almost entirely dependant on home runs to generate runs. The 1950 Cubs hit 161 home runs, second in the league to the Dodgers 194. The Cubs were also second in Isolated Power at .153, .013 better than the league average and .022 better than the Phillies. Despite this strength at the plate, the Cubs were a terrible offensive team. They were dead-last in the NL in runs scored at 643. They had, by far, the lowest On-Base Percentage in the NL (.311), drew the fewest walks, and the lowest Gross Productive Average (GPA) in the game: .240 … The Cubs 643 runs scored under-performs their Base Runs (650), Batting Runs (656) and Runs Created (658). After home runs the only stat they led the league in was strikeouts.

Andy Pafko had an exceptional season with 121 Runs Created (8.88 Runs Created per 27 Outs) for the Cubs, as did 1952 MVP Hank Sauer (96 Runs Created, 6.39 Runs Created per 27 Outs), but the Cubs were too inconsistent at the plate to be the equal of the Dodgers.

If the Cubs offense was forgettable, than their pitching and defense were more so. Led by Bob Rush, who lost twenty games in 1950, the Cubs finished seventh in Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), seventh in strikeouts, sixth in walks allowed, and sixth in ERA. Their lousy pitching was further undermined by a terrible defense. Defensively, the Cubs were the worst team in the NL, with a .694 DER, .007 worse than the Braves and Pirates and .035 worse than the Giants. The Cubs led the NL in errors with 198, 47 more than the Phillies, 61 more than the Giants and 71 more than the Dodgers. This was not a good defensive team. In fact, they allowed a whopping 120 un-earned runs! (.78 UERA)

The Cubs were never really in the playoff picture. After starting the season 3-0, they steadily dropped back in the standings. At the All-Star break the Cubs were 33-38 and ten games behind the Phillies. Their record would just get worse. The Cubs posted the worst post-All Star game record in the NL, going 31-51. On July 21 the Cubs swept a two-game series with the Braves and improved to 39-41, just seven games out of first place. They would lose seventeen of their next twenty-one games. After losing to the Pirates 7-4 on August 10, the Cubs were nineteen and a half games out of first and their season was finished. The Cubs would go 10-19 in September, finishing in seventh place, seven games ahead of the Pirates. The Cubs record since hasn’t been the best.

This season the Cubs are fast-approaching their centennial since their last World Series victory in 1908. Since then, the Cubs lost seven World Series all between 1910 and 1945. After the Cubs lost Game Seven of the 1945 World Series to the Detroit Tigers on October 10, 1945, they wouldn’t make the playoffs for another thirty-nine years! When they finally did in 1984, the Cubs proceeded to lose the NLCS to the San Diego Padres 3-2 despite winning the first two games 13-0 and 4-2. The Cubs have made the playoffs just three times since, losing the 1989 NLCS to the San Francisco Giants 4-1, losing the NLDS to the Braves 3-0 in 1998, and then, humiliatingly, losing the 2003 NLCS to the Marlins after leading the series 3-1 and being just five outs away from victory in Game Six before surrendering eight runs to lose 8-3. The Red Sox were able to pull themselves together after their collapse against the Yankees in Game 7 of the ALCS and win the 2004 World Series, but the Cubs continue to be the loveable losers of Wrigley Field.

Those were the also-rans.

Next, I’ll talk about what happened to the Phillies after the All-Star Break on Tuesday after I get done giving some thoughts on the World Series on Monday.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part VII: The Giants & Dodgers.

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

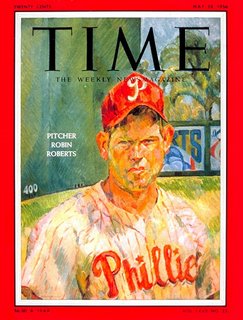

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

(1) comments

Well, the Dodgers and Giants weren’t the only teams competing with the Phillies for the National League pennant. To varying degrees the Boston Braves and St. Louis Cardinals were also in the thick of things in the NL pennant race, while fans in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Chicago dreamed of better days ahead. Let’s look at them, starting with the Braves.

The Boston Braves. I realized something about the 1950 Boston Braves as I examined their stats. This team had a very good pitching staff. Very good. Jim Konstanty may have won the 1950 MVP award, and Robin Roberts may generally be recognized for being the best pitcher in the NL in 1950, but there is an argument to be made that Warren Spahn was the best pitcher in the NL in 1950. Look at FIP ERAs*:

Jim Konstanty: 3.70

Robin Roberts: 3.55

Curt Simmons: 3.53

Warren Spahn: 3.32

* FIP – Fielding Independent Pitching: (13*HR+3*BB-2*K / IP) + League Factor Evaluates a pitching by how he would have done with an average defense behind him by keeping track of things that a pitcher can control (walks, strikeouts, home runs allowed) as opposed to things he cannot (hits allowed, runs allowed).

This was an extraordinarily talented team that boasted a tremendous threesome of Spahn, Johnny Sain and Vern Bickford. Spahn, Sain and Bickford threw 883 of the Braves 1,385 innings (64%) that season. Aside from Roberts 304 and a third innings, nobody threw more innings then Bickford (311 & 2/3), Spahn (293) and Sain (278 & 1/3) in the NL. They went 60-44 and threw 77 complete games. They were an extraordinary trio, but they were all the team had. Their collective ERA was 3.52. The rest of the team was 5.24 …

The Braves also had a good offense, finishing second in the NL in runs scored with 785, 63 more than the Phillies. The Braves were third in the NL in Isolated Power at .142, compared to the Phils .134, and second in Gross Productive Average (GPA) at .253, as compared to the Phillies .248 … The Braves had a very efficient offensive unit. Their 785 runs dramatically out-performs their Base Runs (734), their Batting Runs (746) and their Runs Created (761).

Confused about what I’m talking about? Here are the stats I refer to defined:

Gross Productive Average (GPA): (1.8 * .OBP + .SLG) / 4 = .GPA. Invented by The Hardball Times Aaron Gleeman, GPA measures a players production by weighing his ability to get on base and hit with power. This is my preferred all-around stat.

Isolated Power (ISO): .SLG - .BA = .ISO. Measures a player’s raw power by subtracting singles from their slugging percentage.

On-Base Percentage (OBP): How often a player gets on base. (H + BB + HBP) / (Plate Appearances)

Walks per plate appearance (BB/PA): BB / PA = .BB/PA Avg

Slugging Percentage (SLG): Total Bases / At-Bats = Slugging Percentage. Power at the plate.

Runs Created (RC): A stat originally created by Bill James to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. The formula I use for this article is taken from Bill James Historical Abstract circa 1988, when he developed special formulas for Runs Created based on stats that the MLB kept (e.g., caught stealing wasn't a stat baseball kept track of until 1951). The formula is: [(H + BB + HBP - GIDP) times (Total Bases + .26 * (BB + HBP) + .52 * SH)] divided by (AB + BB + HBP + SH).

RC/27: Runs Created per 27 outs, essentially what a team of 9 of this player would score in a hypothetical game.

Base Runs: Developed by Dave Smyth as an alternative to Runs Created. Here is the formula: (A: H + BB + HBP – HR ; B: (.8 * 1B) + (2.1 * 2B) + (3.4 * 3B) + (1.8 * HR) + (.1*(BB + HBP)); C: AB – H; D: HR) Then simply divide B into B + C, then multiply A to the result and add D.

Batting Runs: Another alternative to Runs Created, developed by Pete Palmer as part of his linear weights system. The formula: (.47 * H) + (.38 * D) + (.55 * T) + (.93 * HR) + (.33 * (BB + HBP)) + (.22 * SB) + (-.38 * CS) + (-.10 * (AB - H)).

The key to the Braves offense was balance. They had five players who hit fourteen or more home runs. The team did not merely rely on Earl Torgeson (123 Runs Created, 7.81 Runs Created per 27 Outs, 114 Base Runs), Sid Gordon (107 Runs Created, 8.27 Runs Created per 27 Outs, 103 Base Runs) and Bob Elliott (103 Runs Created, 7.19 Runs Created per 27 Outs, 99 Base Runs), they also had NL Rookie of the Year Sam Jethroe, who led the NL in stolen bases with thirty-five (twice as many as the Dodgers Pee Wee Reese). The Braves were the second-best offensive team in the NL after the Dodgers. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough.

On May 6 the Braves were in first place with a 10-7 record, and they would steadily hang in the playoff picture for another two months. At the All-Star break the Braves were 42-31, two games behind the Phillies. After defeating the Chicago Cubs 10-2 on August 4 behind Warrn Spahn, the Braves were three games out of first and very much in the thick of the playoff hunt. The Braves then lost ten of their next fourteen games and tumbled to eight games out. The Braves would battle back to try and keep pace with the Phillies, but it was too much. On September 17, 1950, they managed to jump into second place, a half game ahead of the Dodgers and seven and a half behind the Phillies, but the Braves would go 5-11 the rest of the way, while the Dodgers made a 13-5 dash to catch up to the Phillies. I suspect that if you go back and examine the Braves season, you’ll find that the strain of pitching every third day wore Spahn, Bickford and Sain down.

The Braves would leave the Boston area after the 1952 season and journey westward to Milwaukee, where they immediately became the prime challenger to the Dodgers – Giants duopoly, finishing second to the Dodgers in 1953, 1955 and 1956 before breaking through to win the 1957 World Series over the Yankees and grab the ’58 pennant as well. The Braves deserted Milwaukee in 1965 and journeyed to the South to Atlanta, where they became baseball’s sole team inside of the Old Confederacy (excluding Texas) until the Florida Marlins were created in 1993. Until the team’s modern era (since 1990), the Atlanta Braves were an also-ran for nearly three decades.

The St. Louis Cardinals. Back in the 1950s, the St. Louis Cardinals were the extreme western limit of major league baseball. It was simply too far for teams to travel in trains to go that much further west of the Mississippi River. Air travel, which became widely available during the ‘50s, enabled baseball to move west and embrace California and the Mountain West. However until the A’s abandoned Philadelphia for Kansas City in 1955, the Cardinals were baseball’s western team and the southern team as well.

The Cardinals had a lot of proud history going into the 1950 season. They had most recently won the World Series in 1946, defeating the Boston Red Sox in seven games. Prior to 1946, they had captured the NL pennant in 1942, 1943 and 1944, winning the series in ’42 over the Yankees and in ’44 over the cross-town Browns (who would later move to Baltimore and go on to become the Orioles). Even before that the Cardinals had the Gashouse Gang, a goofy collection of players who had captured the NL pennant five times in nine years between 1926 and 1934 and won three World Series.

The 1950 Cardinals would be less fortunate than their 1920s, 1930s and 1940s counterparts. The ‘50’s weren’t a good time for the Cards. 1946 would turn out to be Stan Musial’s last championship. The Cards wouldn’t capture the NL pennant again until 1964, when the Phillies aided their path to the World Series by collapsing at the end of the season.

Jim Konstanty won the 1950 MVP award and was unquestionably vital to the Phillies in their battle for the post-season, however, I think the best individual player in the league in 1950 was the Cardinals Musial. The twenty-time All-Star had won the MVP award in 1943, 1946 and 1948, and finished second to Konstanty in 1950. Musial would be the NL runner-up from 1949 to 1951.

Musial was a phenomenal player. He may not have had the most explosive bat in the league, but he was consistently the most dangerous hitter.

NL Runs Created (1950):

1. Musial (Cards): 149

2. Snider (Dodgers): 133

3. Kiner (Pirates): 130

4. Torgeson (Braves): 123

5. Stanky (Giants): 121

6. Pafko (Cubs): 121

Musial produced 10.75 runs created per 27 outs, tops in the league. That only gives you a brief glimpse at how tough an out Musial was.

Unfortunately for Musial, the Cardinals didn’t have a whole lot else going for them. The rest of the team had aged and atrophied over the three years since the Cards won the World Series. The Cardinals had a decent pitching staff, which finished second to the Phillies in the league in Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), and home runs allowed (0.79 per nine innings, as well as third in league in walks allowed (3.55 per nine innings), and strikeouts (4.00 per nine innings). The Cards didn’t have a lot of pop at the plate after Musial and they didn’t play defense well. As late in the season as July 20, after sweeping both ends of a double-header with 18-4 and 10-3 victories, the Cardinals owned sole possession of first place in the NL. After that, the Cardinals would drop 41 of their remaining 71 games and struggle to remain at .500. The season would end with the Cardinals in fifth place.

The Cincinnati Reds. There wasn’t a whole lot positive for Reds fans in 1950. The team finished sixth, a position it would occupy for the next three seasons as well. The Phillies largely had their way with the Reds in 1950, winning eighteen of their twenty-two games against them, easily the Phillies best performance against any other team in the National League that season.

The Reds did little right in 1950. They finished dead-last in the NL in Isolated Power (ISO) at .116, well under the league average of .140 and the Phillies .131 … The Reds Gross Productive Average (GPA) was nearly the worst as well, at .240, as compared with the NL average of .250 and the Phillies .248. The Reds were last in the NL in BaseRuns with 631, last in the NL in Batting Runs with 638, and last in the NL in Runs Created with 652. They were the second-worst scoring offense in the NL.

Their pitching wasn’t much better, finishing seventh in the NL in ERA, fifth in FIP ERA, seventh in walks allowed (3.86 per nine innings) and sixth in home runs allowed (0.96 per nine innings). The only areas where the Reds excelled at were defense, where the Reds had the third-best DER in the NL – .708 – after the Phillies (.719) and Giants (.729), and strikeouts, where the Reds pitching staff K’d 4.55 batters per nine innings, a terrific number only exceeded by the Dodgers (5.00).

A disastrous May (6-19) saw the Reds occupy the cellar for most of the season. After losing to the Dodgers 8-2 on June 20, the Reds were in dead-last, 15-38 (.283), a whopping eighteen games behind the Dodgers and seventeen behind the Phillies and Cardinals just fifty-three games into the season. The Reds went on to win as many games as they lost the rest of the way (51-49), but the damage was done. A ten-game losing streak from August 18 to August 27 ended any chance the Reds had of a winning season. They limped to a sixth place finish. Their 28-49 record at home (.364, versus 38-38, .500 on the road) kept fans away in droves. The Reds drew 538,794 fans in 1950, nearly 405,597 fewer fans than the Braves, the next-worst team in terms of attendance. The Pirates and Cubs, despite finishing worse than the Reds, attracted well over twice as many fans to their ballparks.

The Pittsburgh Pirates. The 1950 Pirates were an interesting enigma, though they were the worst team in the NL, a distinction they would possess or share until 1958, when they finished in second place and get ready to play in the 1960 World Series. The Pirates would finish seventh or eighth every year from 1950 to 1957, despite having future Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner in the lineup.

Kiner was a remarkable player: just 27 entering the 1950 season, he had hit 54 home runs in 1949 and entered the 1950 season having hit 168 home runs already in his brief career. He hit another 47 in 1950 and drove in 118 runs. Kiner may have been the best hitter in the NL in 1950 (though I think that distinction belongs to Stan Musial), and his presence in the lineup helped the Pirates finish second in Isolated Power and Slugging Percentage and third in Gross Productive Average in the NL. And yet the Pirates were sixth in runs scored. On paper they should have been a pretty decent team at the plate, but no team had a bigger variance between its Runs Created and Actual Runs:

Runs Created / Actual Runs

Reds: 652 / 681 (+29)

Braves: 761 / 785 (+24)

Cubs: 643 / 658 (+15)

Dodgers: 841 / 847 (+6)

Giants: 738 / 735 (-3)

Phillies: 725 / 722 (-3)

Cardinals: 701 / 693 (-8)

Pirates: 737 / 681 (-56)

The Pirates problem simply was that Kiner was their only real threat. Note that 40% of Kiner’s RBIs were of himself: home runs. Kiner drove in just 71 teammates. Compare that to Duke Snider, whose home runs amount to just 30% of his RBIs, or Del Ennis, whose homers were 25% of his RBIs. Kiner had 130 Runs Created in 1950, 18% of the team’s output. Bill James noted that the ’50 Pirates were the most inefficient team of the 1950s in his 2005 Handbook (Page 15), losing fourteen more games than they should have. It was an offensively inefficient team and you have to wonder how frustrated Kiner was playing on the Pirates.

Defensively the Pirates were pretty ordinary. In terms of pitching the Pirates were the worst in the NL: dead-last in terms of ERA (in fact over a half run worse than the next-worst team, the Cincinnati Reds) and dead-last in terms of FIP (a quarter of a run worse than the Cubs). No team got fewer strikeouts (3.66 per nine innings), surrendered more walks (4.05 per nine innings), and only the Dodgers gave up more home runs (1.00 per nine innings).

Interestingly, despite being the worst team in the National League and never really being a factor in the race for the pennant (even as early as June 1, 1950, the Pirates were eight games out of first), the Pirates were third in the NL in attendance, after the Phillies and Dodgers. In fact the Pirates drew just 19,629 fewer people than the Dodgers and 50,768 fewer than the Phillies. The Pirates drew more than twice as many fans as their rivals down the Ohio River, the Cincinnati Reds. Despite being a bad team, they were popular.

The Chicago Cubs. I’ve always thought that the Chicago Cubs are a very strange franchise. Whereas the suffering of the Boston Red Sox inspired Shakespearean pathos thanks to the multitudes of writers who live in or hail from New England, the Cubs have a sort of bland Midwestern happiness to their futility. The Red Sox may have been cursed to fail as spectacularly as they have, but the Cubs are the victims of simple incompetence.

The 1950 Cubs were nothing special, and have no indication to their fans that they had played in the 1945 World Series and nearly won. Their offense was almost entirely dependant on home runs to generate runs. The 1950 Cubs hit 161 home runs, second in the league to the Dodgers 194. The Cubs were also second in Isolated Power at .153, .013 better than the league average and .022 better than the Phillies. Despite this strength at the plate, the Cubs were a terrible offensive team. They were dead-last in the NL in runs scored at 643. They had, by far, the lowest On-Base Percentage in the NL (.311), drew the fewest walks, and the lowest Gross Productive Average (GPA) in the game: .240 … The Cubs 643 runs scored under-performs their Base Runs (650), Batting Runs (656) and Runs Created (658). After home runs the only stat they led the league in was strikeouts.

Andy Pafko had an exceptional season with 121 Runs Created (8.88 Runs Created per 27 Outs) for the Cubs, as did 1952 MVP Hank Sauer (96 Runs Created, 6.39 Runs Created per 27 Outs), but the Cubs were too inconsistent at the plate to be the equal of the Dodgers.

If the Cubs offense was forgettable, than their pitching and defense were more so. Led by Bob Rush, who lost twenty games in 1950, the Cubs finished seventh in Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), seventh in strikeouts, sixth in walks allowed, and sixth in ERA. Their lousy pitching was further undermined by a terrible defense. Defensively, the Cubs were the worst team in the NL, with a .694 DER, .007 worse than the Braves and Pirates and .035 worse than the Giants. The Cubs led the NL in errors with 198, 47 more than the Phillies, 61 more than the Giants and 71 more than the Dodgers. This was not a good defensive team. In fact, they allowed a whopping 120 un-earned runs! (.78 UERA)

The Cubs were never really in the playoff picture. After starting the season 3-0, they steadily dropped back in the standings. At the All-Star break the Cubs were 33-38 and ten games behind the Phillies. Their record would just get worse. The Cubs posted the worst post-All Star game record in the NL, going 31-51. On July 21 the Cubs swept a two-game series with the Braves and improved to 39-41, just seven games out of first place. They would lose seventeen of their next twenty-one games. After losing to the Pirates 7-4 on August 10, the Cubs were nineteen and a half games out of first and their season was finished. The Cubs would go 10-19 in September, finishing in seventh place, seven games ahead of the Pirates. The Cubs record since hasn’t been the best.

This season the Cubs are fast-approaching their centennial since their last World Series victory in 1908. Since then, the Cubs lost seven World Series all between 1910 and 1945. After the Cubs lost Game Seven of the 1945 World Series to the Detroit Tigers on October 10, 1945, they wouldn’t make the playoffs for another thirty-nine years! When they finally did in 1984, the Cubs proceeded to lose the NLCS to the San Diego Padres 3-2 despite winning the first two games 13-0 and 4-2. The Cubs have made the playoffs just three times since, losing the 1989 NLCS to the San Francisco Giants 4-1, losing the NLDS to the Braves 3-0 in 1998, and then, humiliatingly, losing the 2003 NLCS to the Marlins after leading the series 3-1 and being just five outs away from victory in Game Six before surrendering eight runs to lose 8-3. The Red Sox were able to pull themselves together after their collapse against the Yankees in Game 7 of the ALCS and win the 2004 World Series, but the Cubs continue to be the loveable losers of Wrigley Field.

Those were the also-rans.

Next, I’ll talk about what happened to the Phillies after the All-Star Break on Tuesday after I get done giving some thoughts on the World Series on Monday.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part VII: The Giants & Dodgers.

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

The Wiz Kids, Part VII: Focus on the Opposition … the New York teams

The Phillies two strongest foes in 1950 were the two New York teams, the Giants and Dodgers. Little would their fervent fans would realize, but both teams would depart their long-time home in just seven years, just one year removed from a period of time where they would dominate the National League. The Dodgers, the winners of 1947 and 1949 NL pennants, would go on to win the NL pennant in 1952, 1953, 1955 and 1956 before the team left for Los Angeles. The Giants meanwhile, would win the 1951 pennant in dramatic style before winning the ’54 pennant and World Series. They to would leave for the West Coast, arriving in San Francisco for the 1958 season. Aside from the Wiz Kids in '50, these two teams dominated the NL from 1947 to 1956.

The Brooklyn Dodgers.

Roy Campanella. Jackie Robinson. Pee Wee Reese. Duke Snider. Not many starting lineups can boast four Hall of Fame baseball players, but the 1950 Brooklyn Dodgers did. Campanella, Robinson, Resse and Snider combined to form the core of a lineup that was more fearsome than any other fielded in 1950. The Dodgers scored 847 runs that season, 62 more than the Boston Braves, 112 more than the Giants and 125 more than the Phillies. They were easily the most impressive team in the NL offensively. The Dodgers led the NL in nearly every category, from home runs (33 better than the second-place Cubs), to batting average (.272, .007 better than the Phillies), to OBP (.346, .007 better than the Braves), to slugging percentage (.444, .038 better than the Pirates), to stolen bases (77, 6 better than the Braves). They were a fearsome offensive machine that got on base, advanced runners and blasted home runs.

Confused about what I’m talking about? Here are the stats I refer to defined:

Gross Productive Average (GPA): (1.8 * .OBP + .SLG) / 4 = .GPA. Invented by The Hardball Times Aaron Gleeman, GPA measures a players production by weighing his ability to get on base and hit with power. This is my preferred all-around stat.

Isolated Power (ISO): .SLG - .BA = .ISO. Measures a player’s raw power by subtracting singles from their slugging percentage.

On-Base Percentage (OBP): How often a player gets on base. (H + BB + HBP) / (Plate Appearances)

Walks per plate appearance (BB/PA): BB / PA = .BB/PA Avg

Slugging Percentage (SLG): Total Bases / At-Bats = Slugging Percentage. Power at the plate.

Runs Created (RC): A stat originally created by Bill James to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. The formula I use for this article is taken from Bill James Historical Abstract circa 1988, when he developed special formulas for Runs Created based on stats that the MLB kept (e.g., caught stealing wasn't a stat baseball kept track of until 1951). The formula is: [(H + BB + HBP - GIDP) times (Total Bases + .26 * (BB + HBP) + .52 * SH)] divided by (AB + BB + HBP + SH).

RC/27: Runs Created per 27 outs, essentially what a team of 9 of this player would score in a hypothetical game.

Base Runs: Developed by Dave Smyth as an alternative to Runs Created. Here is the formula: (A: H + BB + HBP – HR ; B: (.8 * 1B) + (2.1 * 2B) + (3.4 * 3B) + (1.8 * HR) + (.1*(BB + HBP)); C: AB – H; D: HR) Then simply divide B into B + C, then multiply A to the result and add D.

WHIP – Walks plus hits by innings pitched: (BB + H) / IP = WHIP

ERA – Earned Run Average: (Earned Runs * 9) / IP = ERA

FIP – Fielding Independent Pitching: (13*HR+3*BB-2*K / IP) + League Factor Evaluates a pitching by how he would have done with an average defense behind him by keeping track of things that a pitcher can control (walks, strikeouts, home runs allowed) as opposed to things he cannot (hits allowed, runs allowed).

DER – Defense Efficiency Ratio: (Batters Faced – (Hits + Walks + Hit By Pitch + Strikeouts)) / (Batters Faced – (Home Runs, Walks + Hit By Pitch + Strikeouts)) How often fielders convert balls put into play into outs.

In particular, Duke Snider had an amazing season: 31 home runs, 31 doubles, 10 triples, .321 Batting Average, 107 RBIs, 109 Runs Scored. A sabremetric look at his numbers says a lot more: Snider had a .309 Gross Productive Average (GPA) and a .232 Isolated Power (ISO). Snider led the Dodgers in Runs Created (RC) and Base Runs (BsR):

Runs Created:

Snider: 133

Robinson: 116

Hodges: 116

Furillo: 98

Reese: 90

Campanella: 83

Base Runs:

Snider: 118

Robinson: 107

Hodges: 100

Furillo: 93

Campanella: 83

Reese: 77

The Dodgers best hitter in terms of raw power was catcher Campanella, who had a .270 ISO (31 home runs despite having just 75% of the AB’s as guys like Snider). Their top hitter overall was Jackie Robinson, who led the team with a .315 GPA. #42 only had 14 home runs, fifth on the team, but he did lead the Dodgers in doubles with 39 and drew 80 walks with only 24 strikeouts. Yes, Jackie Robinson struck out in just 4% of his plate appearances. I wonder if anyone was ever as difficult to strikeout as Jackie Robinson*.

* Ok, I checked it out and I think I found someone a little more difficult to K: in 1941 Joe DiMaggio struck out just 13 times in 621 plate appearances. That’s 2%. Still, Jackie Robinson did pretty good in '50!

The Dodgers, however, struggled in many other aspects of the game. In terms of pitching, the Dodgers really struggled. While it is true that the Dodgers led the NL in strikeouts (5.00 per nine innings, 0.45 better than the Reds, 1.03 better than the Phillies), they were fifth in the NL in allowing walks (3.83 per nine innings) and worst in allowing home runs (1.06 per nine innings). Given that the top slugging team in the NL was themselves, that means they must have been very susceptible to the long-ball.

As a consequence they rank sixth in the NL in terms of Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) ERA:

Phillies: 3.89

Cardinals: 3.95

Braves: 4.04

Giants: 4.14

Reds: 4.17

Dodgers: 4.20

Cubs: 4.23

Pirates: 4.50

League: 4.14

This isn’t to say that the Dodgers didn’t have talent. They had Don Newcombe, the firey power pitcher who was every bit as good as the Phillies Robin Roberts:

FIP ERA:

Roberts: 3.55

Newcombe: 3.45

Roberts / Newcombe

HR/9: 0.86 / 0.74

K/9: 4.32 / 4.38

BB/9: 2.28 / 2.52

Newcombe was helped by the fact that he got to face the light-hitting Phillies instead of the Dodgers like Roberts, and that Roberts threw nearly forty more innings than Newcombe, which means that his arm was much more tired. Roberts would later out-duel Newcombe on the final day of the 1950 season to capture the pennant for the Phillies. (see, Part XII of this series.)

The rest of the Dodgers pitching staff was a bust. Preacher Roe, the former Phillie, was nowhere near as good as his 3.30 ERA indicated: his FIP ERA was 4.07. Roe surrendered 34 home runs in 250 innings, 1.22 per nine innings. He was largely saved by good defensive work. After Roe and Newcombe, the quality of the Dodgers staff fell off quickly: poor Ralph Branca, who would go down in infamy as the man who surrendered Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” the next year, in particular struggled in 1950.

The Dodgers pitchers weren’t helped by the fact that the Dodgers fielding wasn’t great: the team Defense Efficiency Ratio (DER) was just .703, which ranked them fourth behind the Giants (.729), the Phillies (.719), and the Reds (.708). The Dodgers appeared to have a strong middle defense with Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson, but looked weak everywhere else.

The Dodgers reliance on slugging as opposed to pitching and defense would come back to haunt them: they went 23-21 in one-run ball games while the Phillies went 30-16. The inability to win close games led to the Dodgers offensive output being wasted: of their 89 victories in 1950, 29 of them were by five runs or more. Their inability to scatter those runs more consistently throughout the season led to feast-or-famine games. Had the Dodgers equaled the Phillies .652 winning percentage in one-run games in their 44 one-run contests, the Dodgers would have won 95 games in 1950 and won the NL by four games.

However, that is pure speculation. The Dodgers did fall short to the Phillies.

The New York Giants.

The New York Giants, in contrast, were a team built around pitching and defense. The Giants led the National League in Defense Efficiency Ratio (DER) by a wide margin:

DER:

Giants: .729

Phillies: .719

Reds: .708

Dodgers: .703

Cardinals: .702

Braves: .701

Pirates: .701

Cubs: .694

The Giants prowess in defense helped obscure the fact that the Giants pitching was good but not great. While the Phillies ERA does rise from 3.50 to 3.89 once you make it defense neutral, it remains the best in the NL by a pretty wide margin. The Giants, in contrast, see their team ERA spike from 3.71 to 4.14, a 0.43 increase. 4.14 is actually the NL average for ERA in 1950, so the Giants fall from the top to the exact middle. In short, the Giants go from having the second-best ERA in the majors to having an average pitching staff once you make their stats defense neutral.

The Giants had some good pitchers in 1950. Larry Jansen was a formidable pitcher, hurling a 3.41 FIP ERA (a 3.01 “real” ERA) in 275 innings of work. Jansen’s 275 innings were fifth-most in the NL, and his 1.07 WHIP was best in the NL. Sal Maglie, who led the NL in ERA in 1950, also turned in an excellent season. Maglie was stingy with surrendering home runs (0.61 per nine innings), but clearly benefited from his defense: his league-leading 2.71 ERA hides a 3.72 FIP ERA.

After Jansen and Maglie the quality of the Giants pitching tails off.

Offensively, the Giants weren’t much to speak of. They hit roughly the league average in GPA: .250. Their Isolated Power was .134, below the NL average of .140 that season. They scored 4.77 runs per game, slightly better than the league average of 4.66 … The Giants probably played above their heads: according to the Base Runs formulas, the Giants over-performed: scoring 735 runs when Base Runs had them at 705. Runs Created actually suggests they slightly under-performed by three runs, however.

The Giants offensive weapon was Eddie Stanky, their second-baseman. Stanky might have been the most under-rated player in the NL in 1950, drawing 144 walks in addition to getting 158 hits and scoring 115 runs. Stanky got on base 314 times in 1950, which led the league, and his OBP was a Barry Bonds-like .460. Not even Richie Ashburn (on-base 245 times with a .402 OBP) could do that. Stanky had 121 Runs Created and 114 Base Runs, roughly 16% of his team’s total in both stats. Without Stanky setting the table for the Giants middle order of Bobby Thomson, Hank Thompson and Monte Irvin, the Giants would have been pretty punch-less on offense.

The next season the Giants continued to be a defense oriented team with decent pitching, but dramatically improved offense, which featured Irvin, who led the league in RBIs with 121 (and had 127 Runs Created), and Rookie of the Year Willie Mays, who hit 20 home runs and had 69 RBIs. After losing to the Phillies 4-0 on August 11, 1950, the Giants swept the next three games against the Phillies and won 39 of their final 47 games. They miraculously closed the gap despite the fact that the Dodgers really didn’t play bad baseball (27-24, .529) over the final two months of the season. The season culminated in Bobby Thomson’s home run and the Giants went into the history books.

I'll comment on the World Series tomorrow if they actually get to play and post Part VIII of the series.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

(0) comments

The Brooklyn Dodgers.

Roy Campanella. Jackie Robinson. Pee Wee Reese. Duke Snider. Not many starting lineups can boast four Hall of Fame baseball players, but the 1950 Brooklyn Dodgers did. Campanella, Robinson, Resse and Snider combined to form the core of a lineup that was more fearsome than any other fielded in 1950. The Dodgers scored 847 runs that season, 62 more than the Boston Braves, 112 more than the Giants and 125 more than the Phillies. They were easily the most impressive team in the NL offensively. The Dodgers led the NL in nearly every category, from home runs (33 better than the second-place Cubs), to batting average (.272, .007 better than the Phillies), to OBP (.346, .007 better than the Braves), to slugging percentage (.444, .038 better than the Pirates), to stolen bases (77, 6 better than the Braves). They were a fearsome offensive machine that got on base, advanced runners and blasted home runs.

Confused about what I’m talking about? Here are the stats I refer to defined:

Gross Productive Average (GPA): (1.8 * .OBP + .SLG) / 4 = .GPA. Invented by The Hardball Times Aaron Gleeman, GPA measures a players production by weighing his ability to get on base and hit with power. This is my preferred all-around stat.

Isolated Power (ISO): .SLG - .BA = .ISO. Measures a player’s raw power by subtracting singles from their slugging percentage.

On-Base Percentage (OBP): How often a player gets on base. (H + BB + HBP) / (Plate Appearances)

Walks per plate appearance (BB/PA): BB / PA = .BB/PA Avg

Slugging Percentage (SLG): Total Bases / At-Bats = Slugging Percentage. Power at the plate.

Runs Created (RC): A stat originally created by Bill James to measure a player’s total contribution to his team’s lineup. The formula I use for this article is taken from Bill James Historical Abstract circa 1988, when he developed special formulas for Runs Created based on stats that the MLB kept (e.g., caught stealing wasn't a stat baseball kept track of until 1951). The formula is: [(H + BB + HBP - GIDP) times (Total Bases + .26 * (BB + HBP) + .52 * SH)] divided by (AB + BB + HBP + SH).

RC/27: Runs Created per 27 outs, essentially what a team of 9 of this player would score in a hypothetical game.

Base Runs: Developed by Dave Smyth as an alternative to Runs Created. Here is the formula: (A: H + BB + HBP – HR ; B: (.8 * 1B) + (2.1 * 2B) + (3.4 * 3B) + (1.8 * HR) + (.1*(BB + HBP)); C: AB – H; D: HR) Then simply divide B into B + C, then multiply A to the result and add D.

WHIP – Walks plus hits by innings pitched: (BB + H) / IP = WHIP

ERA – Earned Run Average: (Earned Runs * 9) / IP = ERA

FIP – Fielding Independent Pitching: (13*HR+3*BB-2*K / IP) + League Factor Evaluates a pitching by how he would have done with an average defense behind him by keeping track of things that a pitcher can control (walks, strikeouts, home runs allowed) as opposed to things he cannot (hits allowed, runs allowed).

DER – Defense Efficiency Ratio: (Batters Faced – (Hits + Walks + Hit By Pitch + Strikeouts)) / (Batters Faced – (Home Runs, Walks + Hit By Pitch + Strikeouts)) How often fielders convert balls put into play into outs.

In particular, Duke Snider had an amazing season: 31 home runs, 31 doubles, 10 triples, .321 Batting Average, 107 RBIs, 109 Runs Scored. A sabremetric look at his numbers says a lot more: Snider had a .309 Gross Productive Average (GPA) and a .232 Isolated Power (ISO). Snider led the Dodgers in Runs Created (RC) and Base Runs (BsR):

Runs Created:

Snider: 133

Robinson: 116

Hodges: 116

Furillo: 98

Reese: 90

Campanella: 83

Base Runs:

Snider: 118

Robinson: 107

Hodges: 100

Furillo: 93

Campanella: 83

Reese: 77

The Dodgers best hitter in terms of raw power was catcher Campanella, who had a .270 ISO (31 home runs despite having just 75% of the AB’s as guys like Snider). Their top hitter overall was Jackie Robinson, who led the team with a .315 GPA. #42 only had 14 home runs, fifth on the team, but he did lead the Dodgers in doubles with 39 and drew 80 walks with only 24 strikeouts. Yes, Jackie Robinson struck out in just 4% of his plate appearances. I wonder if anyone was ever as difficult to strikeout as Jackie Robinson*.

* Ok, I checked it out and I think I found someone a little more difficult to K: in 1941 Joe DiMaggio struck out just 13 times in 621 plate appearances. That’s 2%. Still, Jackie Robinson did pretty good in '50!

The Dodgers, however, struggled in many other aspects of the game. In terms of pitching, the Dodgers really struggled. While it is true that the Dodgers led the NL in strikeouts (5.00 per nine innings, 0.45 better than the Reds, 1.03 better than the Phillies), they were fifth in the NL in allowing walks (3.83 per nine innings) and worst in allowing home runs (1.06 per nine innings). Given that the top slugging team in the NL was themselves, that means they must have been very susceptible to the long-ball.

As a consequence they rank sixth in the NL in terms of Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) ERA:

Phillies: 3.89

Cardinals: 3.95

Braves: 4.04

Giants: 4.14

Reds: 4.17

Dodgers: 4.20

Cubs: 4.23

Pirates: 4.50

League: 4.14

This isn’t to say that the Dodgers didn’t have talent. They had Don Newcombe, the firey power pitcher who was every bit as good as the Phillies Robin Roberts:

FIP ERA:

Roberts: 3.55

Newcombe: 3.45

Roberts / Newcombe

HR/9: 0.86 / 0.74

K/9: 4.32 / 4.38

BB/9: 2.28 / 2.52

Newcombe was helped by the fact that he got to face the light-hitting Phillies instead of the Dodgers like Roberts, and that Roberts threw nearly forty more innings than Newcombe, which means that his arm was much more tired. Roberts would later out-duel Newcombe on the final day of the 1950 season to capture the pennant for the Phillies. (see, Part XII of this series.)

The rest of the Dodgers pitching staff was a bust. Preacher Roe, the former Phillie, was nowhere near as good as his 3.30 ERA indicated: his FIP ERA was 4.07. Roe surrendered 34 home runs in 250 innings, 1.22 per nine innings. He was largely saved by good defensive work. After Roe and Newcombe, the quality of the Dodgers staff fell off quickly: poor Ralph Branca, who would go down in infamy as the man who surrendered Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” the next year, in particular struggled in 1950.

The Dodgers pitchers weren’t helped by the fact that the Dodgers fielding wasn’t great: the team Defense Efficiency Ratio (DER) was just .703, which ranked them fourth behind the Giants (.729), the Phillies (.719), and the Reds (.708). The Dodgers appeared to have a strong middle defense with Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson, but looked weak everywhere else.

The Dodgers reliance on slugging as opposed to pitching and defense would come back to haunt them: they went 23-21 in one-run ball games while the Phillies went 30-16. The inability to win close games led to the Dodgers offensive output being wasted: of their 89 victories in 1950, 29 of them were by five runs or more. Their inability to scatter those runs more consistently throughout the season led to feast-or-famine games. Had the Dodgers equaled the Phillies .652 winning percentage in one-run games in their 44 one-run contests, the Dodgers would have won 95 games in 1950 and won the NL by four games.

However, that is pure speculation. The Dodgers did fall short to the Phillies.

The New York Giants.

The New York Giants, in contrast, were a team built around pitching and defense. The Giants led the National League in Defense Efficiency Ratio (DER) by a wide margin:

DER:

Giants: .729

Phillies: .719

Reds: .708

Dodgers: .703

Cardinals: .702

Braves: .701

Pirates: .701

Cubs: .694

The Giants prowess in defense helped obscure the fact that the Giants pitching was good but not great. While the Phillies ERA does rise from 3.50 to 3.89 once you make it defense neutral, it remains the best in the NL by a pretty wide margin. The Giants, in contrast, see their team ERA spike from 3.71 to 4.14, a 0.43 increase. 4.14 is actually the NL average for ERA in 1950, so the Giants fall from the top to the exact middle. In short, the Giants go from having the second-best ERA in the majors to having an average pitching staff once you make their stats defense neutral.

The Giants had some good pitchers in 1950. Larry Jansen was a formidable pitcher, hurling a 3.41 FIP ERA (a 3.01 “real” ERA) in 275 innings of work. Jansen’s 275 innings were fifth-most in the NL, and his 1.07 WHIP was best in the NL. Sal Maglie, who led the NL in ERA in 1950, also turned in an excellent season. Maglie was stingy with surrendering home runs (0.61 per nine innings), but clearly benefited from his defense: his league-leading 2.71 ERA hides a 3.72 FIP ERA.

After Jansen and Maglie the quality of the Giants pitching tails off.

Offensively, the Giants weren’t much to speak of. They hit roughly the league average in GPA: .250. Their Isolated Power was .134, below the NL average of .140 that season. They scored 4.77 runs per game, slightly better than the league average of 4.66 … The Giants probably played above their heads: according to the Base Runs formulas, the Giants over-performed: scoring 735 runs when Base Runs had them at 705. Runs Created actually suggests they slightly under-performed by three runs, however.

The Giants offensive weapon was Eddie Stanky, their second-baseman. Stanky might have been the most under-rated player in the NL in 1950, drawing 144 walks in addition to getting 158 hits and scoring 115 runs. Stanky got on base 314 times in 1950, which led the league, and his OBP was a Barry Bonds-like .460. Not even Richie Ashburn (on-base 245 times with a .402 OBP) could do that. Stanky had 121 Runs Created and 114 Base Runs, roughly 16% of his team’s total in both stats. Without Stanky setting the table for the Giants middle order of Bobby Thomson, Hank Thompson and Monte Irvin, the Giants would have been pretty punch-less on offense.

The next season the Giants continued to be a defense oriented team with decent pitching, but dramatically improved offense, which featured Irvin, who led the league in RBIs with 121 (and had 127 Runs Created), and Rookie of the Year Willie Mays, who hit 20 home runs and had 69 RBIs. After losing to the Phillies 4-0 on August 11, 1950, the Giants swept the next three games against the Phillies and won 39 of their final 47 games. They miraculously closed the gap despite the fact that the Dodgers really didn’t play bad baseball (27-24, .529) over the final two months of the season. The season culminated in Bobby Thomson’s home run and the Giants went into the history books.

I'll comment on the World Series tomorrow if they actually get to play and post Part VIII of the series.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part VI: Curt Simmons.

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

The Wiz Kids, Part VI: Focus on Curt Simmons

People don’t remember what a fantastic set of pitchers the Phillies had for the 1950 campaign with Konstanty, Roberts and Curt Simmons. I’ve already discussed what made Konstanty, the 1950 N.L. MVP, and Roberts special, but I haven’t yet discussed the third part of the Phillies pitching triad: Curt Simmons.

Curt Simmons story beg ins in Egypt, Pennsylvania, north of Philadelphia near Allentown. Simmons was a high school phenom astonishing baseball scouts with his tremendous abilities. In one game, for example, Simmons K’d 23 batters. With other scouts pursuing his services, the Phillies decided to send the team north to play an expedition game against Simmons high school team, with the idea being that once Simmons was hammered by big league hitters, the demand for his abilities would go down and make him more affordable. When Simmons K’d twelve Phillies in the game, a 4-4 tie, the Phillies suddenly found themselves in a protracted bidding war with several other teams. In the end the Phillies won, forking over an astonishing $65,000 signing bonus for Simmons services. The bonus baby, just eighteen, entered the Phillies farm system in Wilmington, and devoured the minor league hitters he faced. Simmons was promoted to the Phillies and pitched the final game of the 1947 season, hurling a masterful 3-1 complete game victory over the New York Giants, striking out nine Giants and allowing just one run.

ins in Egypt, Pennsylvania, north of Philadelphia near Allentown. Simmons was a high school phenom astonishing baseball scouts with his tremendous abilities. In one game, for example, Simmons K’d 23 batters. With other scouts pursuing his services, the Phillies decided to send the team north to play an expedition game against Simmons high school team, with the idea being that once Simmons was hammered by big league hitters, the demand for his abilities would go down and make him more affordable. When Simmons K’d twelve Phillies in the game, a 4-4 tie, the Phillies suddenly found themselves in a protracted bidding war with several other teams. In the end the Phillies won, forking over an astonishing $65,000 signing bonus for Simmons services. The bonus baby, just eighteen, entered the Phillies farm system in Wilmington, and devoured the minor league hitters he faced. Simmons was promoted to the Phillies and pitched the final game of the 1947 season, hurling a masterful 3-1 complete game victory over the New York Giants, striking out nine Giants and allowing just one run.

Let me start off by saying that I am going to be using a lot of stats in this article. If you are confused about what I’m talking about, then here are the stats I refer to defined:

WHIP – Walks plus hits by innings pitched: (BB + H) / IP = WHIP

ERA – Earned Run Average: (Earned Runs * 9) / IP = ERA

FIP – Fielding Independent Pitching: (13*HR+3*BB-2*K / IP) + League Factor Evaluates a pitching by how he would have done with an average defense behind him by keeping track of things that a pitcher can control (walks, strikeouts, home runs allowed) as opposed to things he cannot (hits allowed, runs allowed).

HR/9 – Home Runs allowed per nine innings: (HR * 9) / IP

K/9 – Strikeouts per nine innings: (K * 9) / IP

BB/9 – Walks per nine innings: (BB * 9) / IP

For the next two seasons Simmons struggled badly. Going into the 1950 season there were many questions about whether Simmons was going to be a good hurler for the Phils: he was 12-23 with a 4.64 ERA from 1947 to 1949. Robin Roberts, in contrast, was just two games shy of a .500 record and his ERA was a full run lower. What is striking about Simmons first two full seasons in the majors is that he was able to keep the ball in the park quite a bit, but that he had major control issues. Here are Simmons stats for those seasons:

1948 / 1949

HR/9: 0.42 / 0.48

BB/9: 5.71 / 3.77

K/9: 4.55 / 5.70

ERA: 4.87 / 4.59

W-L: 7-13 / 4-10

But the next three seasons would be triumphs for Simmons. One of the biggest surprises of the 1950 campaign was how exceptionally dominating Curt Simmons pitched. That season he threw 214 & 2/3 innings and went 17-8 with eleven complete games. His numbers were a major improvement from the ’48 and ’49 campaigns.

1950:

HR/9: 0.79

BB/9: 3.68

K/9: 6.11

ERA: 3.40

FIP ERA: 3.53

W-L: 17-8

Combined with Roberts, Konstanty and the rest of the Phillies staff, Simmons helped the Phillies be the best pitching team in the National League. Simmons made an interesting contrast to Roberts: more of a flamethrowing strikeout artist in contrast to Roberts cool, methodical control pitcher. A contemporary observer stated: “Robin Roberts had less dazzling stuff than Simmons …” (Neyer / James Guides to Pitchers, page 385, quoting Sport Magazine, June of 1964.) Roberts himself appreciated Simmons ying to his yang. Said Roberts: “[Simmons] certainly did not disappoint, throwing harder and with more movement on the ball than anyone I had ever seen. He also had a peculiar delivery that hid the ball from the batter." (Neyer / James, quoting My Life In Baseball by Robin Roberts.)

Who was the better pitcher that season? In many ways, Simmons was as good if not better than Roberts. Take a quick gander at the numbers:

Simmons vs. Roberts: ‘50

FIP: 3.53 / 3.55

ERA: 3.40 / 3.02

HR/9: 0.79 / 0.86

BB/9: 3.68 / 2.28

K/9: 6.11 / 4.32

WHIP: 1.23 / 1.18

Roberts did throw nearly a hundred more innings than Simmons that season and was virtually the Phillies only pitcher down the stretch when they were busy trying to hold onto their slim lead over the Dodgers. So Roberts was the better pitcher in 1950, but Simmons was vital to the reason why the Phillies built a lead in August of 1950 in the pennant race.

The hard throws and the peculiar delivery were Simmons hallmarks as a major leaguer. According to author Will Marshall: “[Simmons] herky-jerky motion prevented batters from picking up the ball readily. More ever, the left-handed Simmons’ cross-fire delivery, which came from the direction of first base, intimidated left-handed hitters. His pitching repertoire consisted of two fastballs – one that took off and another that dipped – an excellent change-up and a hard-breaking curve.” (Neyer /James, quoting Baseball’s Pivotal Era: 1945-1951.) Simmons force and the trajectory he delivered it made it a difficult pitch to put into play for a hit even when someone could make contact. Said the Giants Whitey Lockman: “[Simmons] ball was a heavy ball and even when I hit it, I felt like I hit a rock.” (Neyer / James.)

Thanks to North Korea’s decision to invade South Korea in the summer of 1950, Simmons was forced to sign up with a National Guard unit to avoid being drafted by the Army. Unfortunately for Simmons, his National Guard unit was called up in mid-September. The effect Simmons absence on the Phillies roster was immediate. Down the stretch the Phillies saw their six-game lead evaporate as their pitching staff grew perilously thin. Roberts actually had to start three of the Phillies final five games of the season and was so worn down from the dramatic victory over the Dodgers on October 1, that he was unable to start Game One of the World Series. As you’ll see in a future installment of this series, the Phillies defeat in the 1950 World Series was due to a lack of offense instead of a lack of quality pitching, but Simmons absence in the Series impacted the team.

Simmons remained in uniform in 1951, missing the entire season. A crucial reason for why the 1951 Phillies fell short to the Giants and Dodgers was Simmons absence: the decline in Jim Konstanty’s performance, the decline in Del Ennis’ performance and the overall slip in the quality of the Phillies offense put more pressure on a pitching staff that was suddenly much, much thinner than it had been.

Simmons returned in 1952 and had probably his best season as a Phillie:

1952:

HR/9: 0.49

BB/9: 3.13

K/9: 6.31

ERA: 2.82

FIP ERA: 2.84

W-L: 14-8

WHIP: 1.19

1952 was also probably Robin Roberts finest season as a pitcher: 28-7, 2.59 ERA (2.86 FIP). With Simmons back the Phillies once more had the best pitching staff in the majors, with a team ERA of just 3.07, nearly a half run better than the second-place Dodgers at 3.53. Unfortunately the Phillies finished in fourth place, nine and a half games behind the Dodgers thanks to the Dodgers fearsome offense, which the lighter-hitting Phillies could not match.

The ’52 campaign was a major triumph for Simmons: he started the 1952 All-Star Game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. It was the third straight year a Phillie had done so (Roberts started in ’50 & ’51), and it would be the first of Simmons two All-Star Game starts.

Simmons got off to another great start in 1953, pitching a one-hitter against the Boston Braves where he got 27 consecutive batters out after allowing a lead-off single. Unfortunately, Simmons suffered a freak injury in 1953 when he accidentally ran over his foot with his lawn mower and injured in big toe. As in 1950, as in 1952, Curt Simmons wouldn’t reach the magical number of twenty wins in 1953. He finished strong, but it wasn’t quite on par with ’50 and ’52:

1953:

HR/9: 0.65

BB/9: 3.10

K/9: 5.22

ERA: 3.21

FIP ERA: 3.49

W-L: 16-13

WHIP: 1.24

Simmons turned in another good performance in 1954, going 14-15 with a 2.81 ERA, his career low ERA. Despite his impressive performance – nonwithstanding the mirage of his win-loss record – Simmons didn’t make the ’54 All-Star roster. Simmons struggled in 1955, going just 8-8, before returning to his old form in 1956 with a 15-10 record. Here are Simmons stats for those seasons:

1954 / 1955 / 1956

FIP: 3.37 / 4.14 / 3.50

ERA: 2.81 / 4.92 / 3.36

HR/9: 0.53 / 1.04 / 0.78

BB/9: 3.49 / 3.47 / 2.96

K/9: 4.45 / 4.02 / 4.00

WHIP: 1.28 / 1.53 / 1.27

W-L: 14-15 / 8-8 / 15-10

In 1957 Simmons returned with the finest season he had since ’52. Once more Simmons started in the All-Star Game, the seventh time in eight years that a Phillie pitcher had started. Unfortunately, the ’57 Phillies just weren’t very good, scoring the second-fewest runs in the N.L. that season. Roberts went 10-22. Despite Simmons great season, the Phillies went 77-77 and finished eighteen games behind the first-place Milwaukee Braves. Here are Curt’s stats:

1957:

HR/9: 0.47

BB/9: 2.13

K/9: 3.91

ERA: 3.44

FIP ERA: 3.09

W-L: 12-11

WHIP: 1.25

What struck me as interesting was that Curt was more of a strikeout artist throughout his career, especially in contrast to Roberts, a control pitcher who was more apt at not surrendering walks than getting strikeouts. ’57 was a major change for him: it was, by far, the lowest walks per nine innings pitched he surrendered in his career. It was also the fewest strikeouts he had gotten per nine innings in his career. Compare his walks and strikeouts in 1950, 1952 and 1957:

1950 / 1952 / 1957

BB/9: 3.68 / 3.13 / 2.13

K/9: 6.11 / 6.31 / 3.91

Those are startling changes. He was becoming a different pitcher. Unfortunately, 1957 was pretty much the end of the line for Curt Simmons as a Phillie. In 1958 he went 7-14 with a 4.38 ERA which was much worse than his 3.20 FIP ERA. Simmons hurled just ten innings in 1959 and was released by the team in 1960, whereupon the St. Louis Cardinals wisely snapped him up. Simmons suddenly became an anchor on a very strong Cardinals team. In 1964 Simmons turned in his finest performance since 1957, going 18-9 (a career high in wins) with a 3.43 ERA. A look at Simmons stats from that season shows how he morphed from being a flamethrower to a Robin Roberts-like control pitcher:

HR/9: 0.89

BB/9: 1.80

K/9: 3.84

Simmons enabled the Cardinals to sweep up from behind the Phillies and stun the ’64 Phils by coming from six and a half games back on September 20, 1964, to win the pennant. On September 30, 1964, Simmons defeated Jim Bunning 8-5 at Busch Stadium, scattering five hits over eight innings, striking out two Phillies and not allowing a walk, in a masterful game that ran the Phillies losing streak to ten games and effectively ended their season and completed one of the darkest moments in Phillies history. It was the Cards eighth consecutive victory. Simmons started games three and six for the Cardinals, both defeats, although Simmons wasn’t the losing pitcher in their 2-1 loss in Game Three when Mickey Mantle drove a Barney Schultz knuckleball out of the field for a home run in the bottom of the ninth. After being denied an opportunity to play in the ’50 World Series, '64 was Simmons sole taste of post-season glory.

Simmons left the Cards during the ’66 season and briefly pitched for the Chicago Cubs, alongside his old Phillies teammate, Robin Roberts. The 1967 season was his last. Simmons retired that season.

In the final analysis I think a few things are noteworthy about the life and career of Curt Simmons: he was a very integral part of those teams that the Phillies fielded in the 1950s that came close to the edge of competing yet consistently fell short. He’d probably be more remembered in the history of Philly sports if he had won twenty games, something he never did and Roberts did six consecutive seasons from 1950 to 1955. Curt Simmons deserves to be remembered as a dominant pitcher and a big part of Phillies baseball in the 1950s. It is too bad that the Korean War interfered with his season in 1950, because he almost certainly would have won twenty games that season, and might have won twenty and helped the Phillies compete in 1951 as well.

It is a sad, "what-if" of history. Good work, Curt.

Previous Installments of the Wiz Kids:

Part V: Robin Roberts.

Part IV: The first half of the 1950 season.

Part III: Jim Konstanty.

Part II: Eddie Sawyer.

Part I: The Path to 1950.

Prolouge.

(1) comments

Curt Simmons story beg

ins in Egypt, Pennsylvania, north of Philadelphia near Allentown. Simmons was a high school phenom astonishing baseball scouts with his tremendous abilities. In one game, for example, Simmons K’d 23 batters. With other scouts pursuing his services, the Phillies decided to send the team north to play an expedition game against Simmons high school team, with the idea being that once Simmons was hammered by big league hitters, the demand for his abilities would go down and make him more affordable. When Simmons K’d twelve Phillies in the game, a 4-4 tie, the Phillies suddenly found themselves in a protracted bidding war with several other teams. In the end the Phillies won, forking over an astonishing $65,000 signing bonus for Simmons services. The bonus baby, just eighteen, entered the Phillies farm system in Wilmington, and devoured the minor league hitters he faced. Simmons was promoted to the Phillies and pitched the final game of the 1947 season, hurling a masterful 3-1 complete game victory over the New York Giants, striking out nine Giants and allowing just one run.